# Week 1 - Introduction to Compilers

Last edited: 2026-01-28

A program that translates source code written in one programming language into another programming language. Commonly the target programming language is machine code that is executable.

A similar but different concept to a Compiler is an interpreter.

A program that directly executes source code written in one programming language.

Programming languages such as Python, and JavaScript are interpreted languages. Whereas languages such as C, Java, Rust and Go are compiled languages.

Interpreted languages tend to be slower as they have to do the ‘interpreting’ whilst running the program. In comparison, compiled languages are faster as they can be compiled into machine code and then executed.

# Why compile?

Machine code or assembly have very few abstractions. Therefore, programming in them is very slow and error prone. Higher level languages add in abstractions such as data types, functions, classes and objects. So the main reason to have a higher level language is to speed up the development process.

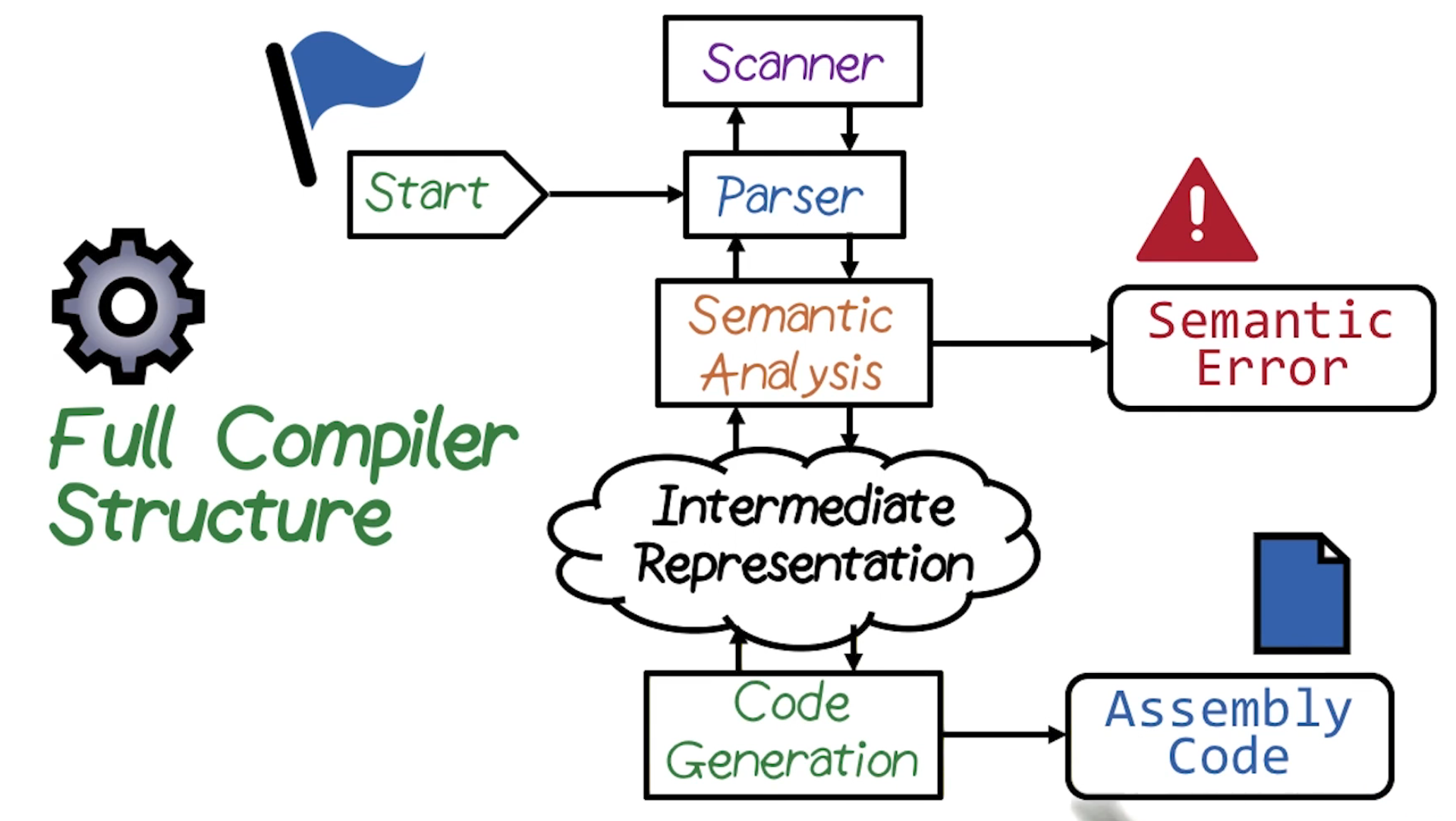

# Compiler structure

The broad structure of the compiler is as follows:

Front-end: This is responsible for analysing the source code to check it follows the languages rules correctly. If it does, it passes the source code into an intermediate form.

Middle-end (optimiser): This takes the intermediate form and tries to optimise it in a platform independent way.

Back-end: This takes the optimised intermediate form and converts this into the target language in a machine specific way. For example, if compiling into assembly using the instruction set available for that CPU.

# Front-end

We will focus on the front-end for now. There are 3 main steps to the front-end:

Input: The source code in the form of a string.

Scanning: The source code is broken down into tokens.

Tokens: Think of this as known words or phrases that are valid in the language.

Parsing: We check the tokens against the grammar of the language to check they are in a valid order. For example, does an add sit between two numbers?

Semantic analysis: The tokens are checked against the semantics of the language to make sure they ‘make sense’. For example, if two numbers are added are they of the same type?

# Scanning

To scan through the source code, we use 2 main things:

Token buffer: This is a buffer of letters that have been passed to the scanner.

Lexicon: The definition of a legal token.

To scan the document, the scanner reads letter by letter adding it to the token buffer. At each stage we use the languages lexicon to check if what is in the token buffer could still be part of a valid token. If so, we move onto the next letter. If not, we check if the token buffer contains a valid token. If so we pass that out as our next token. If not, we throw an error.

Note here we only check if the token buffer could be a token by itself - not if it fits in the larger context of what is already passed, that is for later components. This algorithm is called the ’longest match’ algorithm.

# Parsing

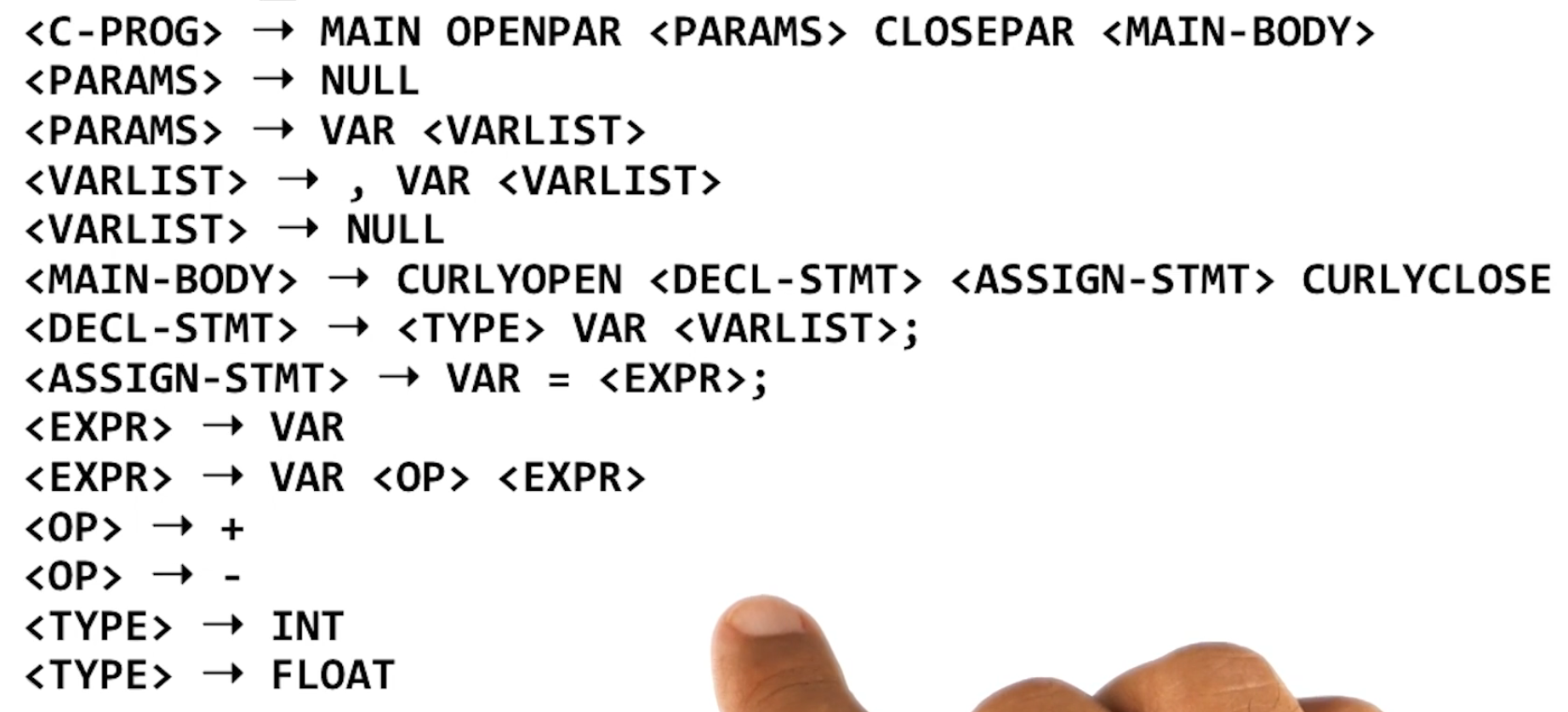

To start parsing these tokens, we need to define the grammar of the language. An example of this is below.

This defines the syntax of the language.

For example, a = b + c is syntactically valid but a = b +- is not.

It does this through a recursive definition.

This will be discussed later, for now we assume we have the right rule.

When recursively applying rules, we may need to ’expand’ clauses. For example with the main operator above:

MAIN OPENPAR <PARAMS> CLOSEPAR <MAIN-BODY>

When parsing we can choose how to expand the <PARAMS> either using the null expansion (no parameters) or the recursive VARLIST definition.

# Parser ambiguity

Grammars can be written to be ambiguous or unambiguous. A Grammar is ambiguous where rules could be applied in multiple ways to give valid results. For example:

$$ \begin{aligned} 2 * 2 + 3 & = (2 * 2) + 3\\ & = 7\\ 2 * 2 + 3 & = 2 * (2 + 3)\\ & = 10\\ \end{aligned} $$Another example closer to code might be:

if a then if b then print("1") else print("2")

There are two possible ways to group the else with the if. Using the outer if we would get:

if a then (if b then print("1") ) else print("2")

This means if a is true and b is false then we print nothing. Otherwise we can group using the second if.

if a then (if b then print("1") else print("2"))

In this case if a is true and b is false then we print 2.

We will go on to see it’s possible to take an ambiguous grammar and make it unambiguous if not slightly more verbose!

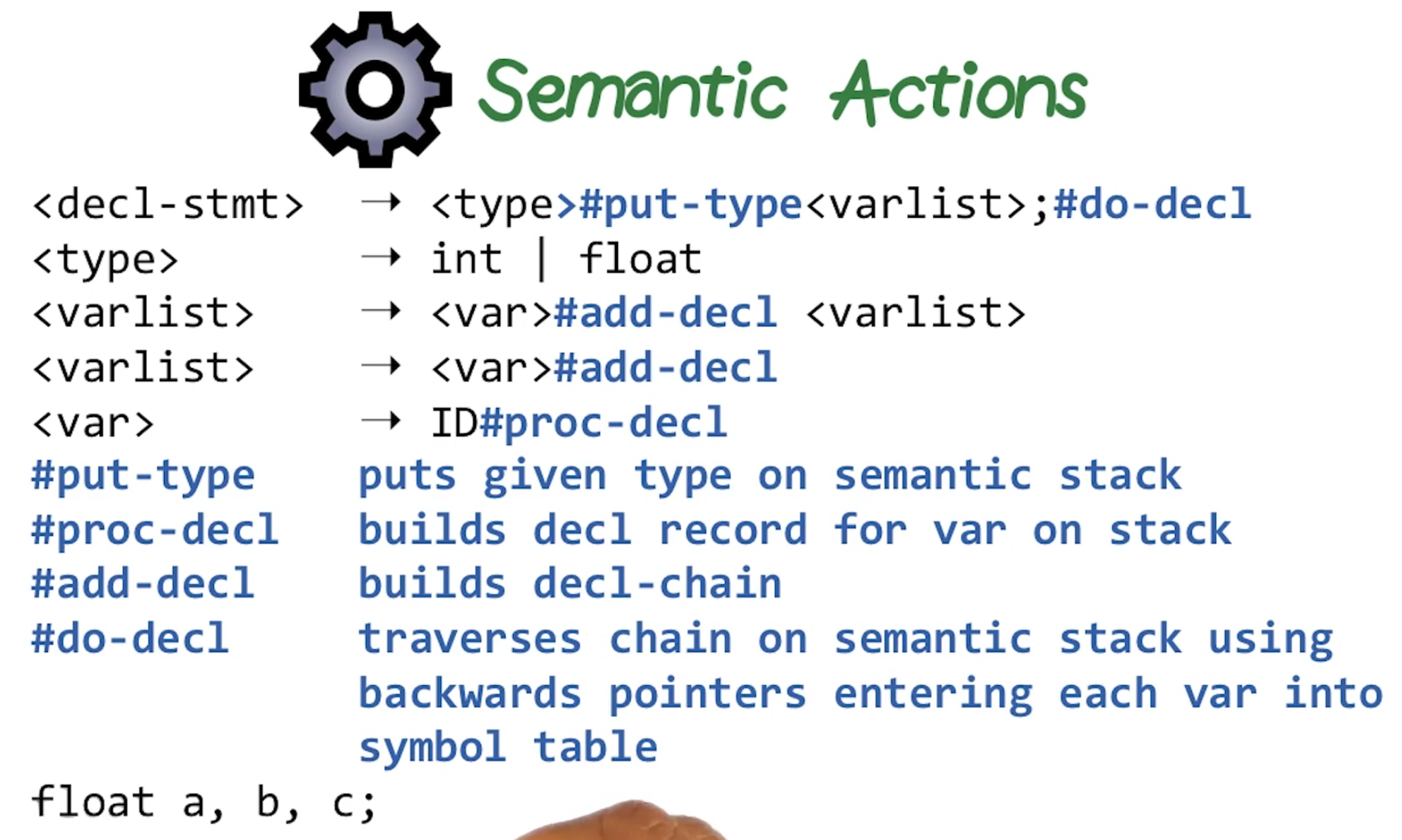

# Semantic analysis

The semantic analysis of the language checks that the program is valid. In short this checks the types of the variables are correct for the operations. It also checks that the variables we are using are defined. It does this using the Symbol table.

The symbol table stores all our variable names, types and which scope they are defined within.

Now we have our symbols stored, we can carry out semantic actions upon them. This is done using the following flow:

If a new variable is declared, add it into the symbol table.

Look up variables in the symbol table.

Do binding of looked up variables. (i.e. checking the scoping rules)

Do type checking compatibility for variables.

Keep the semantic context of processing.

For the last step, what we mean is when breaking down operations like a + b + c we not only need to carry out the operation a + b first we will need to store a temporary record t1 of its type in the symbol table.

This enables us to use the same logic on (a + b) + c as if it was an operation between two symbols t1 and c.

Generally semantic analysis is embedded in the grammar. This means when the parser adds each token onto a semantic stack. When there is enough information on the semantic stack to perform a semantic action - it gets carried out. You can see an example of this below:

The actions in blue can be thought of as ‘functions’. In the example above we have a declaration stack that we can keep adding variables to before we add them to the symbol table with a given type.

There are many types of semantic actions, such as:

Checking: Binding, Type compatibility, Scoping, etc.

Translation: Generate temporary values, propagate them to keep semantics.