# Week 9 - RT and Multimedia

Last edited: 2026-01-28

# Week 9 - RT and Multimedia

# Time sensitive Linux (TS-Linux)

Historically, OS systems have been optimised to handle ’throughput orientated’ tasks such as databases and scientific applications. Though in modern OSs we have to prioritise ’latency orientated’ tasks such as playing games and synchronous audio players. These tasks need guarantees that events can happen at a given time.

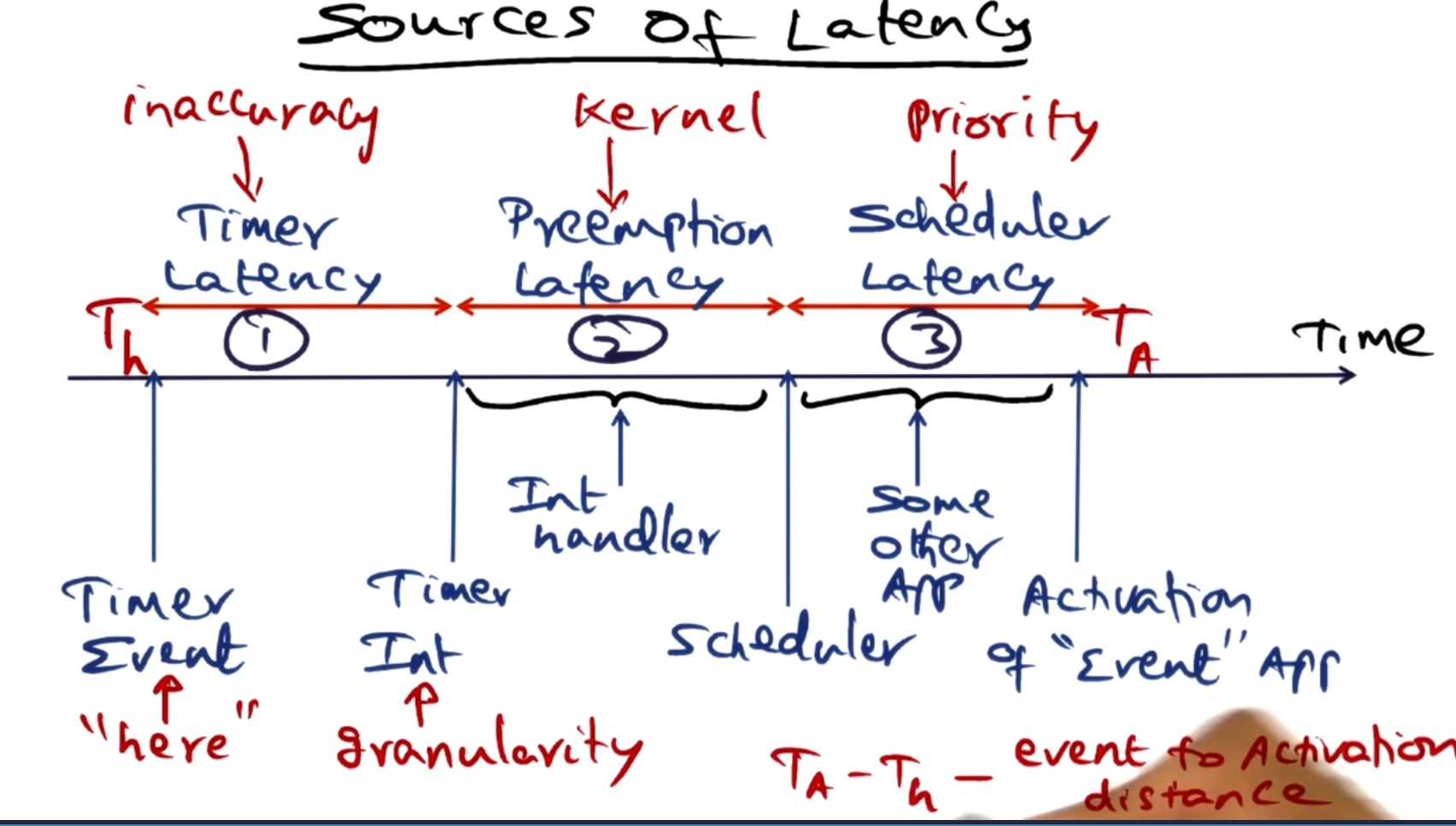

# Sources of latency

There are 3 categories of latency between an event happening and us switching to the application to handle that event:

Timer latency: Due to the inaccuracy of the timer mechanism there is a difference between when the timer should have gone off and when the interrupt was actually thrown. For example, periodic timers tend to have a 10ms granularity for when they can be scheduled.

Preemption latency: After the interrupt has happened the kernel may be stuck doing a task that can not be interrupted, such as manipulating core kernel data structures or handling a higher priority interrupt.

Scheduler latency: When the scheduler takes control after the interrupt is processed it may not choose to schedule the task that needs to handle the interrupt as there may be a higher priority task waiting. So we need to wait for this task to be the highest priority task on a queue.

The difference between when the event should have been scheduled and the actual time the processes was switched into is called the event to activation distance.

A time sensitive OS wants to reduce the event to activation distance as much as possible for tasks that are time sensitive.

# Choice of timer

There are different types of timers we can choose from. These each come with pros and cons.

- Periodic timers: These timers fire on a particular periodicity.

- Pro: Predictable and simple to implement.

- Con: Event recognition latency caused by the granularity of this timer.

- One shot timers: These timers fire once and then are disabled.

- Pro: No event recognition latency.

- Con: There may be added overhead switching at a given point to handle the event instead of in a natural break.

- Soft timers: These timers fire at convenient points in time, such as when the kernel is switched to for system calls or scheduling.

- Pro: Zero overhead for handling the timer.

- Con: Polling overhead on each switch and latency as there are no guarantees the kernel will be switched to.

It would be good if we didn’t need to have these payoffs and could get all the upsides. This is what the ‘firm timer’ achieves.

# Firm timers

Firm timers take a middle stance between one-shot timers and soft timers. They are configured to happen at a particular time, but they have an overshoot window in which it is allowed to be late. Within the window between when it was supposed to go off and the overshoot value, if the kernel is switched to then we handle the timer. However, if we reach the end of the overshoot window we handle the timer like a one-shot timer.

This has the advantage of the soft-timers low overhead in most cases but the advantage that we know it will happen at a given time.

# Implementation

There is a timer queue data structure which is a sorted list of timer tasks. These have a key for the time they are meant to trigger at and a value as the entry point for the task they are supposed to run.

The one-shot timers are supported by the APIC timer hardware. This is a hardware timer that gets decremented each clock cycle and throws an interrupt when it reaches zero. Reprogramming these timers takes only a couple of cycles so they offer a efficient one-shot implementation. Using a 100 Hz processor, this effectively drops the timer latency to 10 nanoseconds - but functionally the time taken to field the interrupt takes longer than this and is a bigger source of the timer latency.

The soft timer part of the implementation means that a lot of these one-shot timers are reprogrammed and never raise an interrupt.

# Preempting one-shot timers with periodic timers

If we have one-shot timers with large distance between them and a periodic timer running then we can use the periodic timers to trigger the one-shot timers early. This way we stop the overhead from happening from the one-shot timers.

Won’t the periodic timer going off trigger the soft timer mechanism anyway? Why is this a special case?

The firm timer mechanic reduces the timer latency - next we look at other forms of latency.

# Preemption latency

There are different approaches to reducing this latency:

Explicit insertion of preemption points in the kernel.

Allow preemption anytime the kernel is not manipulating shared data structures.

These two approaches can be combined to define a lock-breaking preemptible kernel. This idea is to break all kernel critical sections into smaller blocks:

Manipulating shared data structures.

All other actions taken in the critical section.

This breaks the critical section into smaller parts allowing the timers to interrupt these actions.

# Scheduling latency

This latency is caused by not being able to switch to the timer task fast enough. TS-Linux reduces this in two ways.

# Proportional period scheduling

In the OS we have defined time quantums we allow tasks to run for, T. In addition to this we let tasks define the ‘proportion’ of a time quantum they need to run for, Q. With this knowledge the OS can schedule tasks together that fit into one time quantum.

This allows TS-Linux to reserve a proportion of each time quantum for latency sensitive tasks. This reduces the scheduling latency as timer-based tasks get a boost in their priority relative to time insensitive tasks.

# Priority scheduling

Suppose we have 3 tasks T1 > T2 > T3 which are ordered by priority. Priority inversion, is where T1 gets blocked by T2 as it has a blocking section where it reaches out to T3. Here the desired behaviour would be to run T1 until it blocks on T3 - then run that until T1 completes. However, as T3 is lower priority than T2 the correct operation of T1 gets blocked by T2 jumping in the middle.

Priority scheduling accounts for this. If a high priority tasks blocks on another - the lower priority task takes the priority of the task that is waiting for it. This ensures the highest priority tasks complete first and do not get blocked by medium priority tasks.

# Persistent Temporal Streams

In the previous section we looked at how to deal with time sensitive applications in commodity hardware. This section will move to looking at handling them in large scale services.

On a single machine, we would use the pthreads library to write parallel programs. In distributed systems we would instead use a sockets API for this task. However, this is too low level for large scale applications - so we want to develop a framework for distributed real time applications.

# Novel multi-media applications

Novel multi-media applications follow the below structure:

The uses sensors such as cameras, radars, noise sensors to gather data about the world.

These sensors are distributed and communicate over the internet.

There is normally computationally intensive real-time processing of the data (in some cloud cluster).

This computation leads to actions either within the sensors or for other entities in the systems, which could involve humans.

There is a common action loop that happens:

Sense: Collect data from the sensors.

Prioritise: Decide what information is important or relevant.

Process: Pass this data into a useful format for making decisions.

Act: Trigger actions based on the output, this can be effecting the sensors or other systems.

Within an airport you will have on the order of 1000’s cameras and other sensors. Traditionally these were all processed by humans in a control room. However, more modern airports are using automatic systems to pick up anomalies and track activity throughout the airport.

These systems face common challenges:

Infrastructure overhead: The amount of data coming from the sensors is overwhelming, so you need a way to prune the data at the source so not to overload your core network.

Cognitive overhead: If humans or even programs are making decisions we need to prioritise the information that is relevant to that decision - so as not to over complicate the decision.

Tolerance for errors: We need to minimise both false negative but also false positives, for fear people distrust the system or ignore alerts.

A system that addresses these challenges needs to:

The programming model needs to allow the domain expert to focus on the domain and not the framework. Therefore, ease of use and the right level abstractions is important - simplicity is the key.

Seamless integration of resources on the edge of the system (the sensors) and the core of the system (the cloud).

Correct temporal ordering of events happening at different sensors. This includes temporal reasoning; the image may be captured at one time step but processed later - it may even integrate into the core much later. Though this information still needs to be integrated with information that might be working on a different time scale.

Integration of live data and historical data. For example, you may have a speeding car today and you will want to know if it has been involved in any incidents over the past couple of days.

Scale: The system has to scale from writing a tracking algorithm on 1 camera to using the same system on 1000 cameras.

# PTS programming model

The PTS model has two core components:

A thread: This is used for execution of a program.

A channel: This is used to store messages between threads.

Threads listen to and write to channels. Although channels use socket like terminology, they are in fact more like a database. They associate an item in them to a time it was added to the channel. This way threads can use time based queries on items within a channel. These channels and threads can form large computational graphs.

To add an item to a channel a thread calls put(item, timestamp).

Whereas to get an item from a channel a thread calls get(lower_bound, upper_bound), this will return all items between the lower and upper bound.

There are other predicates like, get latest item or closest item to a timestamp.

Quite often there will be related channels: For example, the camera, audio, door sensor for a given room.

In these cases we define a ‘stream group’ that indicates these are all related.

To do this we just need to choose one channel which will be the ‘Anchor’ stream (with the others being dependent).

We can then use the groupget function on the Anchor stream to get all the related events.

The channel is what makes this programming model suitable for this use case. The channel:

Can be anywhere in the system.

Can be accessible from anywhere.

Has a network-wide unique name.

Uses time as a first class entity.

Persists streams under App control.

Seamlessly goes from live data to historical, using the same API.

This is all handled by the PTS library under the hood.

# PTS implementation

The channel abstraction is implemented in 4 layers:

Live channel: This is a queue of the latest items that have been added to this channel.

Interaction layer: This moves items from live into a historic queue using the persist trigger. This also supports get queries that span across live and historical data.

Persistence layer: This does the heavy lifting of taking historical items and pickling then saving them appropriately. Users can choose how to pickle different types of objects that can be stored on this channel.

Backend layer: This is the physical storage of historical data. There is a choice of backend MySQL or a choice of file systems.

This is all managed by worker threads that are running within the library, these pick up tasks given by the triggers. For example when a thread calls put on a new object this generates a new item trigger, which is responsible for moving an item into the live channel. The user can also configure garbage collection triggers to automatically clean out old data if it is not being saved down into the historical data. This is normally handled by a separate garbage collection thread.