# Week 7 - Distributed subsystems

Last edited: 2025-10-26

# Week 7 - Distributed subsystems

In this lesson we look at 3 different distributed subsystems. Whilst the subsystems themselves might not be used - the ideas that go into creating them are good take away messages.

# Global Memory System (GMS)

The idea of the GMS was introduced in a paper called “Implementing Global Memory Management in a Workstation Cluster”, when referring to a paper throughout we are talking about this paper. The key idea in GMS is to use the spare memory within a LAN network as another level of cache before going to disk. At the time of the paper being written (1995) sequential access to the disk took 3.6 ms whereas random access took 14.3 ms. In contrast, you could get a round trip to another machine in 2.1 ms - providing a significant speed up.

Note: This was in an era of HDDs however with modern SSDs the speeds are much better and the cost of DRAM has decreased. However, the ideas from GMS are still relevant.

With GMS, the memory hierarchy is as follows:

CPU cache,

local DRAM,

remote GMS, then

Disk.

This will functionally work by splitting the DRAM on each machine into two parts: the local working set, and the shared global memory. The local working set will always have priority over the global memory. We will also make the restriction that any page that is saved into the remote GMS has to be clean. If a node goes down, this should not harm the correct functioning of any of the other nodes on the system.

# Handling page faults

There are multiple different cases that can occur during a page fault. Here we always assume the page fault hits the remote GMS. We go through these cases 1-by-1.

# Case 1: Common case

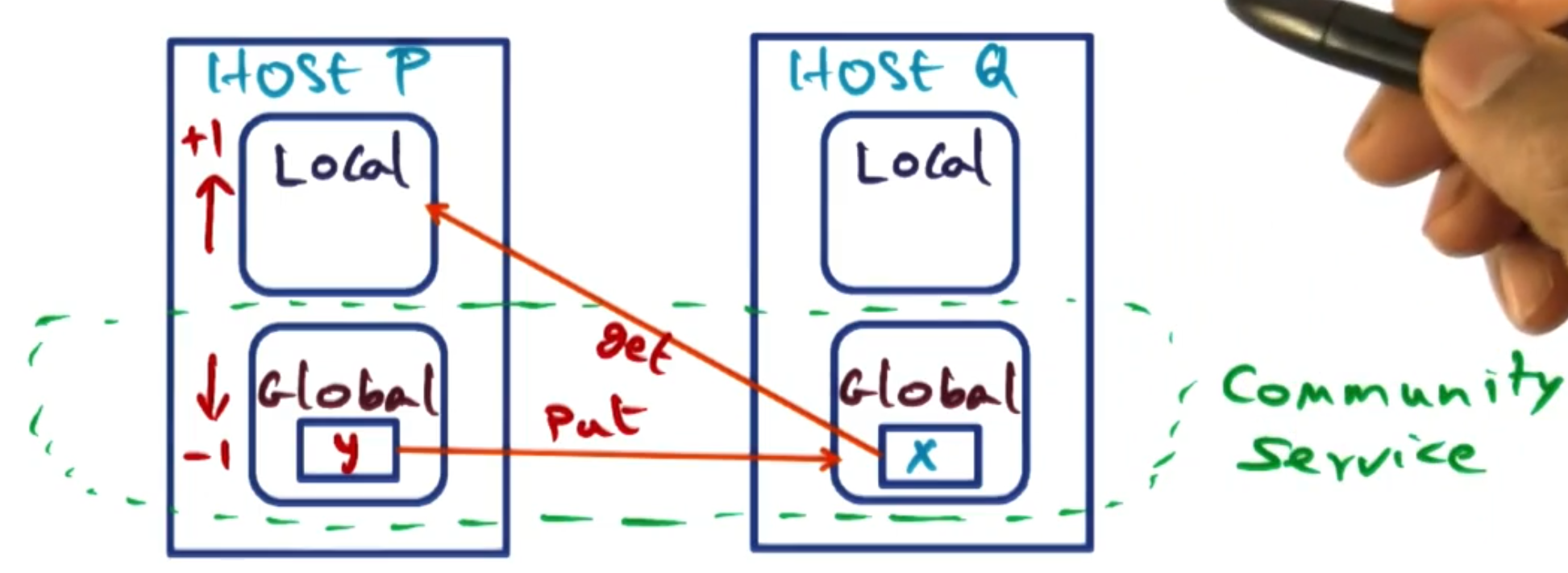

Suppose host P page faults on page X. Host P has its memory split between local pages and a non-zero amount of global pages. We assume another host Q has page X in its global memory. In this case, Host P will increase its local partition by 1 page by selecting a page y from its global partition. Host P and Q then swap: P sends y to Q (which becomes global on Q), and Q sends X to P (which becomes local on P).

# Case 2: No global memory on host

This is the same setup as above but Host P has no global partition. In this case, Host P swaps its LRU local page (which must be clean) with the faulted page X from Host Q. Host Q’s local/global memory balance remains unchanged.

# Case 3: Getting from the disk

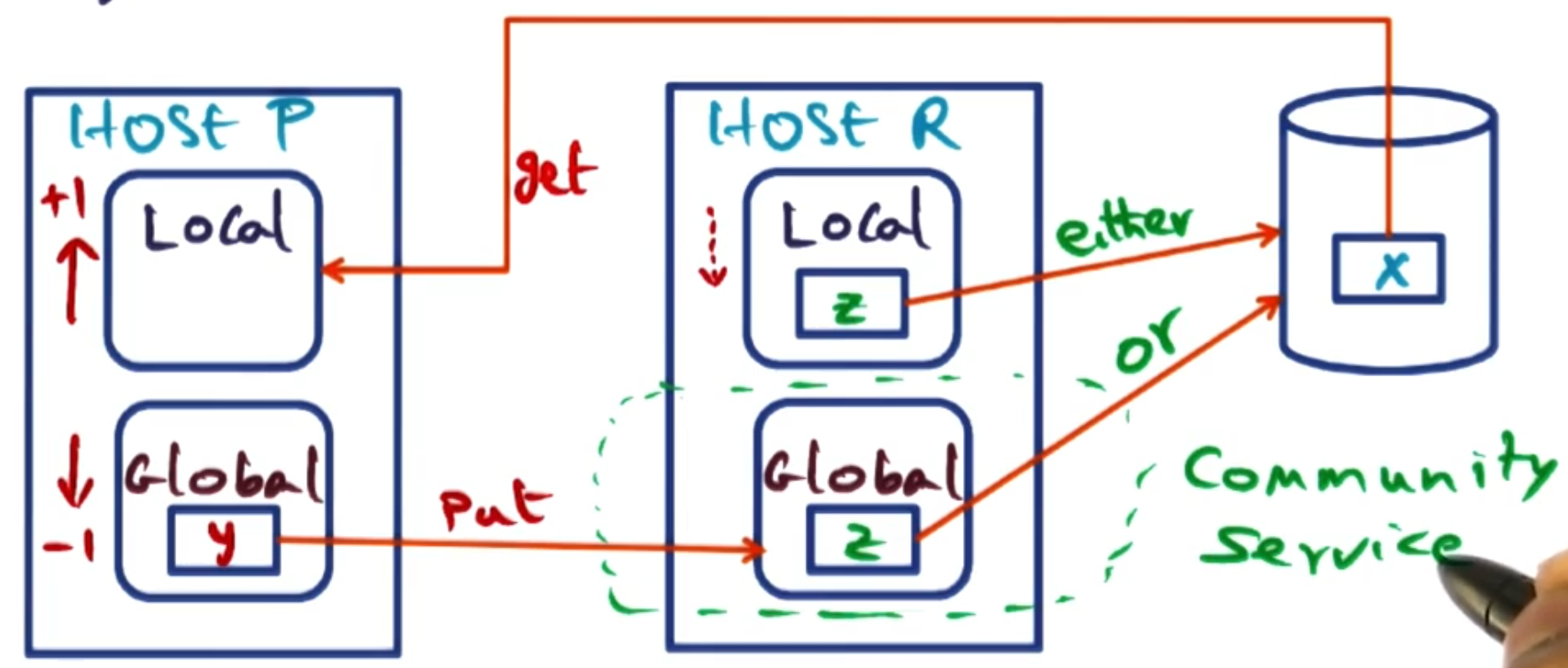

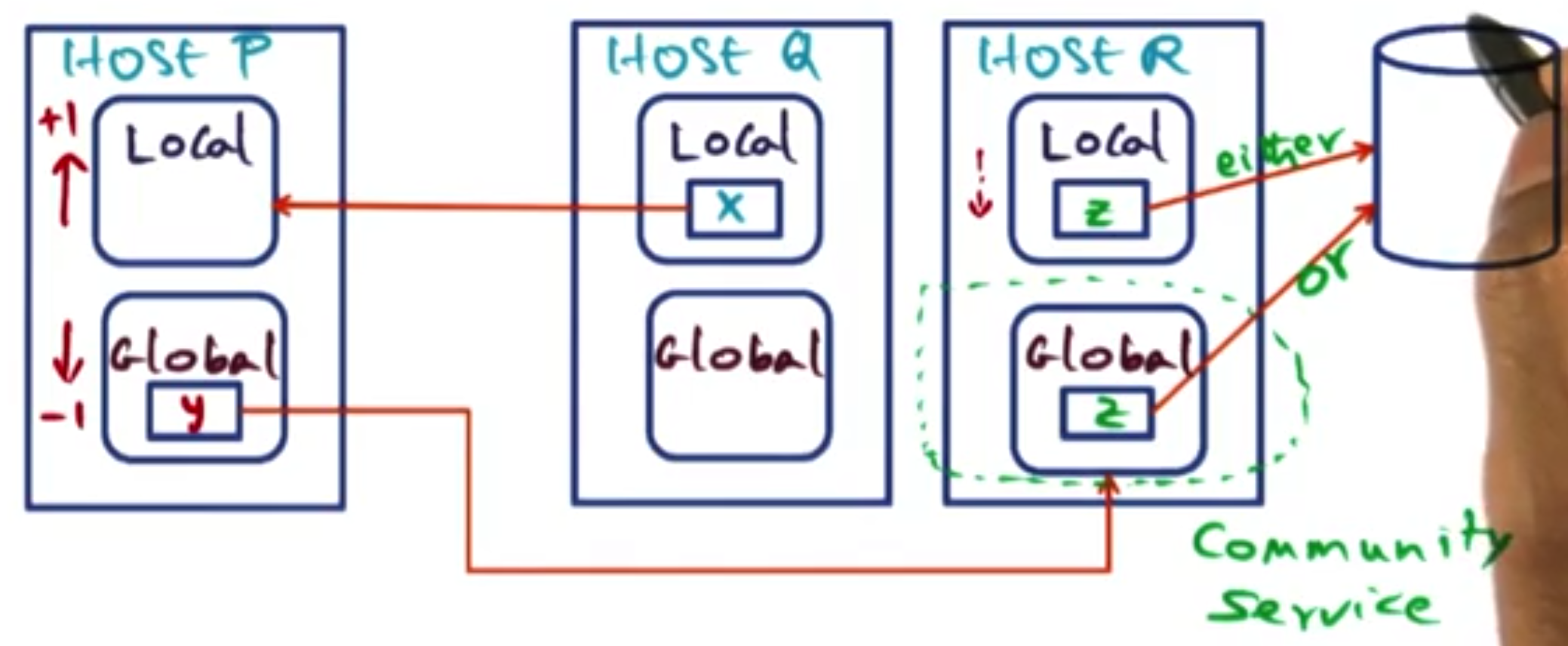

Suppose host P page faults on page X. It has a split of memory between local and a non-zero amount of global memory. However, page X is not in the GMS, so it must be fetched from disk. This increases the local partition of P by 1 page. If none of host P’s pages are the oldest in the cluster, it will need to evict a page y from its global partition. To evict, it identifies host R (which has the oldest page Z in the cluster) and sends y to host R. Host R then evicts its oldest page Z, which happens in one of two ways:

- If Z is clean (in either the global or local partition), it is simply discarded.

- If Z is dirty (and in the local partition), it is written to disk before being discarded.

# Case 4: Actively shared pages

Suppose host P & Q are sharing a page X. However, host P does not currently have it in its local memory and it faults on it. Therefore, host Q will send it over to host P. However, this then kicks off the whole of case 3 - as this page may as well have come from the disk.

# Age management

The scenarios above assume we know where the oldest page in the entire GMS is. In reality, we do not know this - however we aggregate information about age in epochs. These epochs are defined by a max time duration T and a max number of page replacements M.

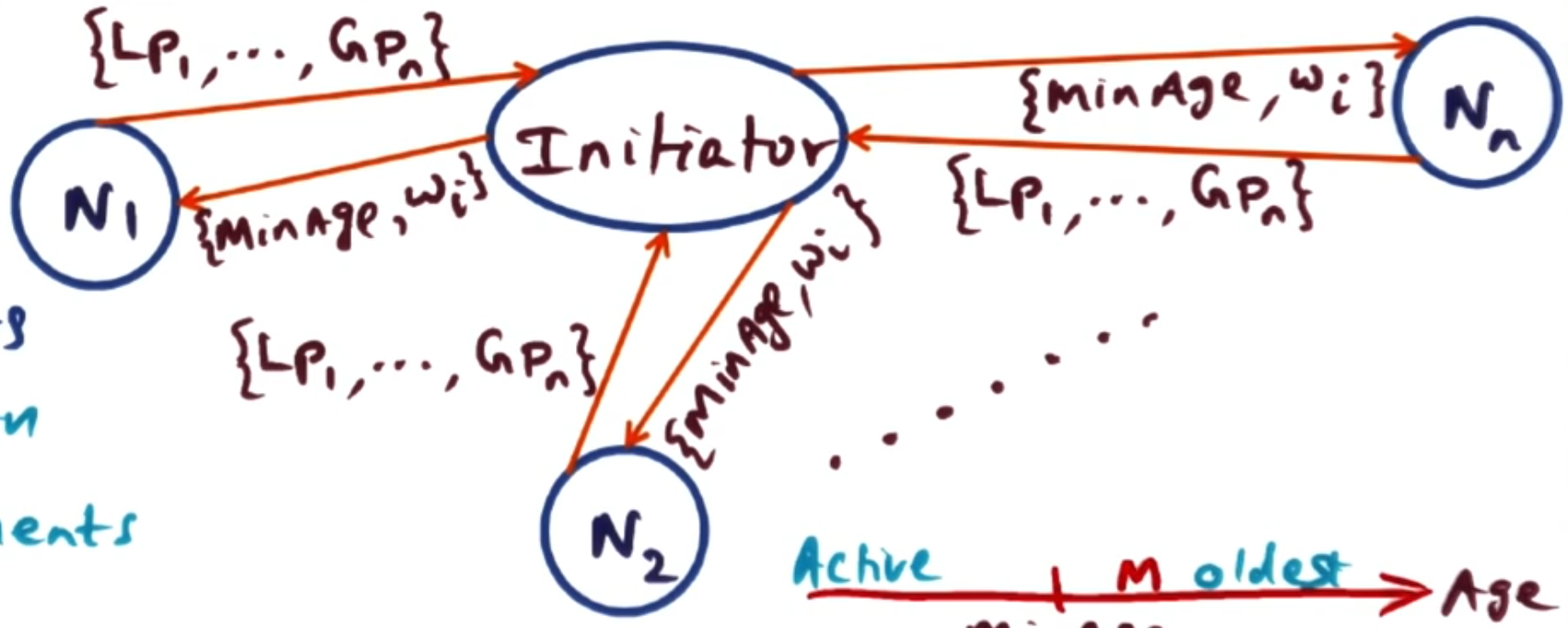

The system also allocates a manager node for the GMS. This is distributed and changes with each epoch. This is best to ensure this works as a distributed system but also to not put too much management work onto a single node.

To start a new epoch, the current manager (or initiator) collects the age of all the pages (both global and local) on all nodes. It then identifies the M oldest pages in the whole network, setting the (M+1)th oldest page as the minAge for this epoch. We then have found our M pages that will be evicted during this epoch. Then it works out for each node the proportion of the M pages that node has, call this $w_i$. Then the initiator sends to each node in the network the minAge and the mapping from node to the proportion of the evicted pages that node has $i \to w_i$. So every node knows every other node’s $w_i$. The node with the largest $w_i$ becomes the manager for the next epoch - since each node has all the $w_i$ values, everyone knows who the new manager is.

Each node then can use the minAge to separate its pages into ‘active’ pages and ‘old’ pages. When a page fault happens, it can locally decide if it should evict or store globally a page by looking at its age. When evicting a page, it uses the weights to decide which node to send it to - it can sample a node from the distribution randomly, which evens out the load proportional to the ages of its pages.

# Implementation in unix

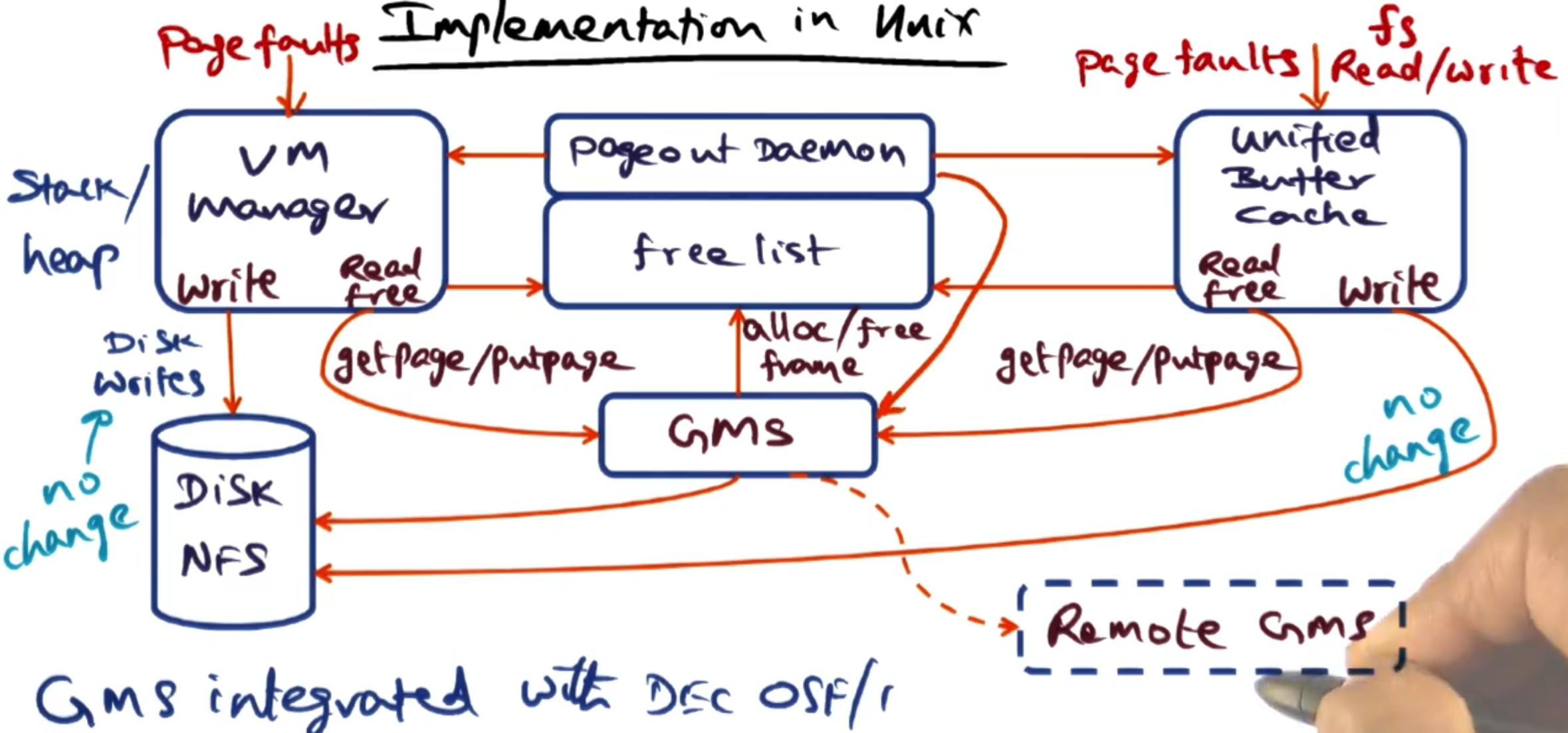

The paper uses a Unix OS called OSF/1 where they changed two key components: the virtual memory manager and the unified buffer cache (UBC) - this system is used to cache the pages of the disk.

The additional two components on the layout above are:

Pageout daemon: Evaluates pages in DRAM to see if it can page them out to the disk.

Free list: List of free pages in DRAM.

Then to implement GMS we need to alter the checks that happen when a page fault happens. The GMS component will handle checking on the remote network if the page exists and all other management needs - but this needs to be ‘plumbed in’.

Here you can see all the handling of free pages goes through the GMS.

The largest technical challenge to overcome is to understand the ‘age’ of each page in memory. The CPU accesses pages ‘anonymously’ through hardware - so there is not an easy way to track the age of each page. They solve this by modifying the TLB handler to flush the TLB once a minute, then a daemon samples the per-frame bits periodically to estimate the ages of different pages. If a page is accessed, it will be loaded into the TLB.

# Data structures

Now pages of memory are distributed across the network - we will need to be able to ‘find’ them in the network. So for each VA we create a UID associated to that page (which as it is clean must exist on the disk somewhere) by adding together:

IP address of the host,

Disk partition,

i-node number, and

offset.

This is derived from the VM and UBC.

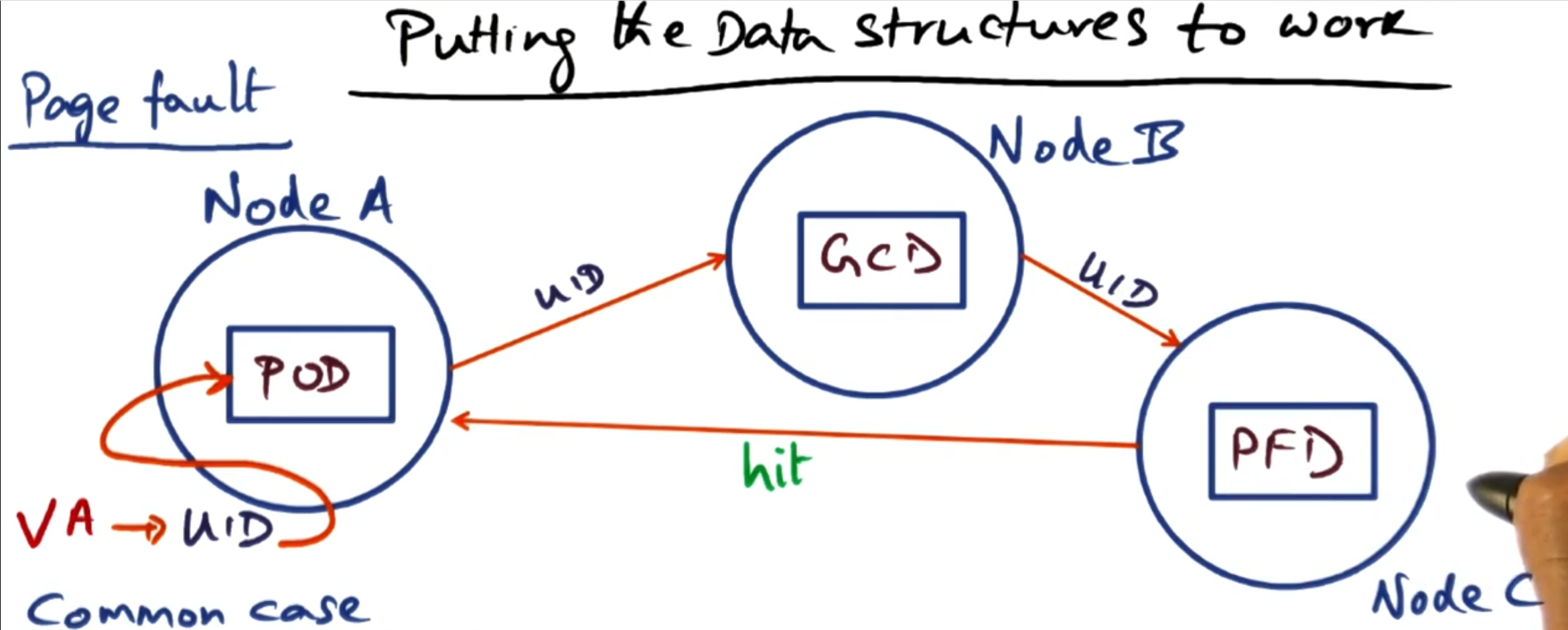

Now we want to go from the UID to the location on the network. To do this we use multiple hash tables to reduce the amount of memory we need on each machine to run the GMS.

Page Frame Directory (PFD): This maps from the UID to the PFN on the local machine. Each entry contains information about the physical page frame, LRU statistics, and whether the page is local or global. Note: Only pages present on this node are in the PFD.

Global Cache Directory (GCD): This maps from the UID to the location of the node that contains the PFD entry for that UID. The GCD is a distributed hash table (each node stores a portion of it). This allows the location of the PFD to be dynamic.

Page Ownership Directory (POD): This maps from the UID to the location of a node that contains the GCD entry for this UID. This is replicated across all nodes - so they can always do this lookup. Whilst not completely static, the POD should only update when nodes join/leave the network.

It may seem like a lot of indirection, whereas we could just go from POD to PFD. However the GCD enables the node that contains the PFD to be dynamic without having to update a table on every node for any change.

Whilst this may look like a lot of network activity to retrieve a page - in most cases each node looks after the GCD for its pages. Therefore Node A and Node B are the same, cutting one of the connections out.

Note: This means the owner of the PFD (i.e. the owner of that page of shared memory) needs to tell the GCD owner when it changes the state of the page.

This communication between the PFD and GCD owner can cause misses in the system above. In this case, we will need to run the search again to get the updated information from the GCD.

The last exceptional case is when the POD information is out of date as the GCD has changed locations. This will happen when nodes leave/join the network - then the host will need to wait for the POD update before retrying the loop.

# Page eviction

When evicting pages, you don’t do this one by one or at the time of the page fault. Instead, this is batched up and handled by the paging daemon when the number of free pages falls below a certain threshold. When the GMS handles this, it batch changes lots of pages all at once to reduce costs. In this case, it will need to find new homes for the pages using the node weights, and update the GCD for the new page locations.

# Distributed Shared Memory (DSM)

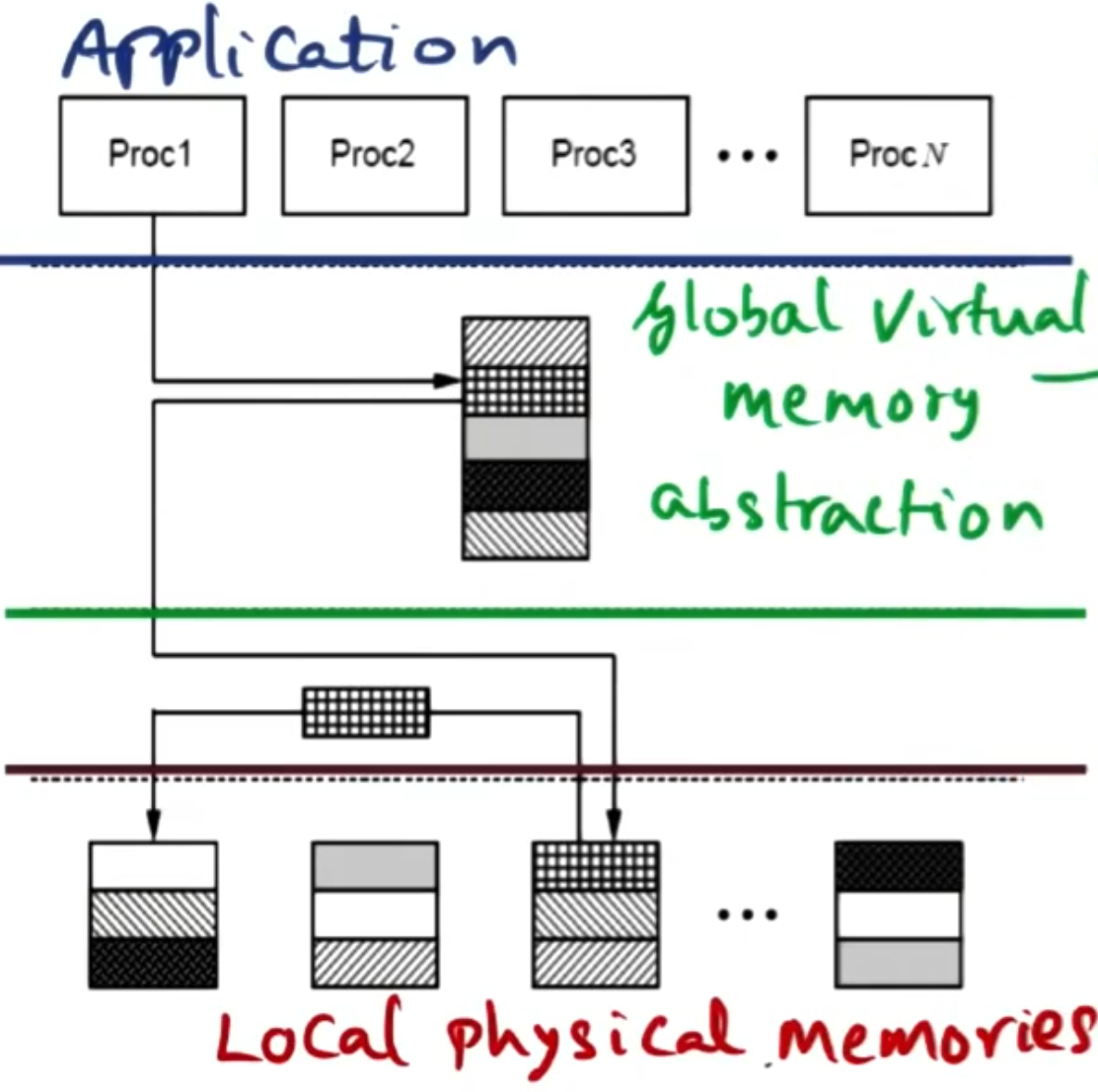

There have been multiple attempts to make writing parallel application easier. Most commonly are packages such as MPI or OpenMP which make the process of sharing work across multiple nodes easier. However, either these work for nodes that are sharing memory or you need communication between different processes to use message passing. If we wanted to apply these techniques to distributed computing on different machines, we would need users to use message passing as there is no shared memory. This provides a barrier to parallelizing programs in a distributed manner, as they would need to rewrite or rethink their application to use message passing. So instead there was an attempt to create a distributed form of shared memory (DSM).

In this section we look at a paper called “TreadMarks: Shared Memory Computing on Networks of Workstations”.

# Shared memory constructs

In programs that use the same memory we use locks and barriers to ensure consistency. These will need to be generalised for our shared memory system.

Though this forms 2 different types of operations, either data change operations or synchronisation operations (e.g. locks or barriers). Whilst working on the same system where hardware guarantees cache consistency the synchronisation constructs and the data they are guarding at the OS level do not need to know about each other. Though this breaks down in a distributed system, even if a lock is working correctly sequential consistency on data writes is not enough. If a lock L is protecting some data A and one process changes A with L, then another process obtains L to change A further - we want to ensure the second process sees the change to A. One way to handle this would be to force consistency on every read/write operation - this would ensure the critical section was always visible to each node - however this is very cumbersome. To handle this issue, we introduce a new consistency model.

Definition: Release consistency works by ensuring that at the point at which a lock L is released all nodes are consistent with one another.

Release consistency works correctly in the distributed setting. This also means we can reduce the number of synchronisation operations to just the ones we need. The downside of this is that every lock release forces all the nodes to be consistent - which can still be too expensive. In the lock example, only the second process needs to find out about the update - not all the nodes.

Definition: Lazy release consistency (Lazy RC) works by any process acquiring a lock must be consistent with the node that released it before it acquires it.

With Lazy RC we reduce the number of nodes needing to maintain consistency from all nodes to just 2. This dramatically reduces the amount of communication needed to maintain consistency. Though this comes with the downside that consistency is needed to be obtained before a thread can progress with its work. Whereas with Release consistency we can run the consistency in the background if other nodes don’t use the variables in the critical section.

# Software DSM

In a distributed system each node has its own memory. Though the goal is for these different nodes to act like they have shared memory. This means each node thinks it has access to all the memory within the application. Then the software DSM needs to intervene to make this happen.

When processes share memory on the same system, they share memory at the level of variables. However, across a network that would be too expensive as every read/write hardware operation would need to run software to verify consistency. Instead, we want to share memory at the level of pages.

When sharing memory on the same system the hardware or kernel is responsible for carrying out consistency. In a distributed model we need to distribute the responsibility for maintaining consistency. To facilitate this, we use distributed ownership - where each node is responsible for carrying out maintenance for the memory it owns. If a page it owns is on another node - it is responsible for making sure these pages are kept consistent. This ownership needs to be known to all the nodes - so on page fault, they know who to go to to get the latest copy of the page.

Note: The owner of the page may not have the page, but it should know where to go to find the page.

# Single writer multiple reader protocol

To facilitate sharing with coherency, some people use a single writer multiple reader (SWMR) protocol. Here, if you want to write to the page you need to do the following:

Tell the owner of the page you want write access,

The page owner invalidates all copies of the page, then

The page owner lets you know you are safe to write to the page.

The big issue with this pattern is false sharing can cause pages to ping back and forth with lots of invalidation. Suppose within the page there are two unrelated variables two processes are writing to.

# Multiple writer protocol (TreadMarks)

Here we are using Lazy RC to maintain consistency. Suppose we have the following:

In P1

Lock(L);

edit pages x,y,z

Unlock(L);

We calculate the page diffs $x_d, y_d, z_d$ after the lock is released. Suppose a new process P2 wants to acquire the lock L. Then process P2 will invalidate (but not remove) its local copy of $x, y ,z$. Then the next time it needs to read $x$ it will collect all diffs of $x$ since its last read. This can be more than one if multiple processes have written to $x$ since last time it synchronised. Then it applies the diffs to its copy of $x$.

Notice this means that the DSM software needs to keep track of which pages are associated to which locks - this is introducing the association between data and synchronisation.

This becomes multiple writer by allowing different locks to be associated with the same page. If a second lock $L2$ is also associated to $x$ when $L$ is used we explicitly DO NOT request the diffs from $L2$ and assume the application developer has done the work to ensure these operations do not overlap.

Note: If two locks read and write to the same part of a page, then we are into a data race but this is a user issue - not a concern for the DSM system.

# Implementation

All pages start off write protected, so we can trap into the DSM software on writes. When a process has acquired the lock and tries to write to a page x, the system makes a ’twin’ of x as it was at the point of lock acquisition. Then all writes happen to the original copy of the x. After the lock is released the DSM software write-protects the original copy of $x$, then uses the twin to calculate a runlength encoded diff of $x$ compared to the twin copy. This is then stored to send to other users of the lock $L$, and the twin is then deleted.

Note: There does need to be a bit of diff garbage collection that gets ran. If too many diffs exist for a single page - these get compacted into the original copy and all versions of that page are invalidated. This is an optimisation to reduce the amount of memory needed by the DSM system.

# Non-page-based DSM

There are some solutions that are not page-based for DSM.

Library based DSM: We use a library that allows ‘consistent variables’ then writes to these variables trap into library code to run consistency. Doing this at the level of variables stops false sharing issues that the multi-writer protocol was getting around.

Structured DSM: This instead of using OS support is a library that offers APIs to cause synchronisation to happen to structs.

# Scalability

As with all shared memory systems, DSM has scalability issues. This gets worse as we increase the number of nodes in the system - more time is spent maintaining consistency. Therefore the old adage is still true for DSM - “Shared memory systems work best when you don’t share memory.”

Ultimately, DSM is really a dead concept but structured DSM did take off as a way to reduce the complexity of writing distributed programs.

# Distributed File Systems (DFS)

There are lots of different structures for network file systems (NFS). Though if it uses a single central server for controlling read/writes and metadata management that will quickly become the bottleneck. Therefore, distributing the file system across multiple nodes is a good way to scale out the file system.

The goal of a DFS then is to distribute the responsibilities of a NFS across multiple nodes. This increases I/O rate of the cluster and cache memory foot print. Though there are the challenges of maintaining consistency across multiple nodes and handling failures.

# Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks (RAID) storage

RAID storage uses multiple disks to store data. It will chop a file up into different chunks and store each chunk on a different disk. Then it will store an error correcting code (ECC) for that file on another disk. The ECC gives some level of recovery from failures. Putting across multiple disks allows for higher I/O rates as multiple disks can be read/written to in parallel.

The draw backs of RAID are the cost of maintaining more disks. The other key issue is small files - if you cut a small file into even smaller chunks then reading it off all the different disks is slower than just having saved the file on one disk.

# Log structured file system (LSFS)

In a LSFS, we write all the changes to files instead of the files themselves. This means we can batch lots of changes all together into one log. We then can reconstruct files by reading the log.

This is useful to do for multiple reasons:

All reads and writes are sequential - which is fast on HDDs.

All writes can be optimally sized to get around having to write small changes to the disk.

Functionally this works by keeping the current log in memory and saving the cache to disk after a given period or once the file is maxed out. Over time, we will find our old logs have been overwritten by newer changes - therefore we need to do garbage collection intermittently to keep logs on the disk fresh.

A downside to this is that we need to read the whole log to reconstruct any file - which can be slow. Normally, we will cache files we have done a full read file so subsequent reads are fast.

A journaling file system is similar to LSFS but it also keeps the data files, and applies the journal (which are the logs) intermittently.

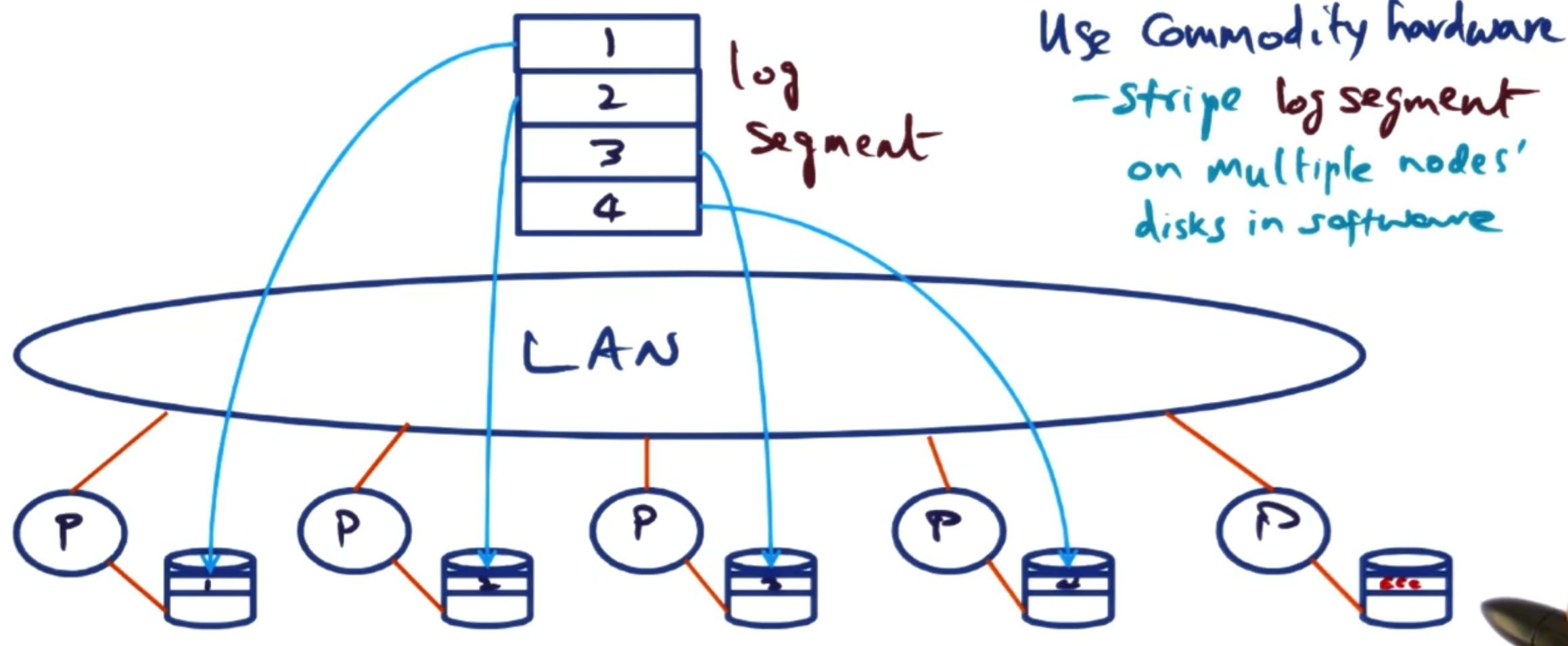

# Software RAID

This combines the ideas of RAID and LSFS.

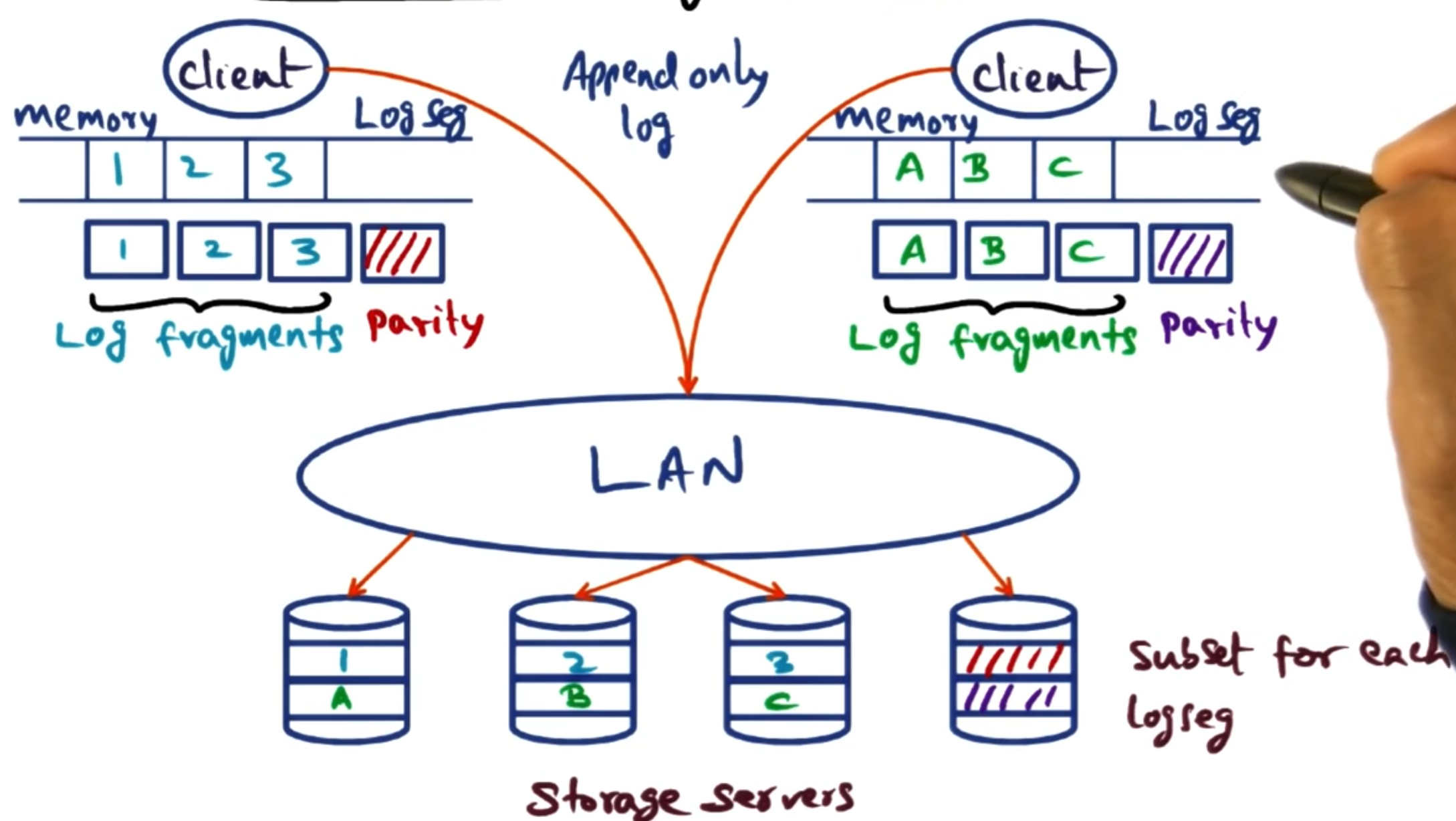

This was first implemented in the Zebra file system. We will run a NFS but save files to a distributed log. When we need to save the log we use different nodes on a LAN network as the different hardware disks in a RAID system.

# XFS

Next we will look at XFS - which is a distributed NFS that uses the ideas from before and others:

Log based striping (software RAID),

Cooperative caching,

Dynamic management of data + metadata,

subsetting storage servers, and

distributed log cleaning.

We will go through the other ideas next.

# Dynamic management

In traditional NFS, servers have a lot of things cached in memory to speed up writes:

File metadata,

File caches, and

Client cache directory (how each client is handling the files - these are considered distinct from one another).

This causes an issue if one server holds ‘hot files’ as there will be a lot of memory pressure on this server. In comparison you may have another server, which is not being accessed at all - wasting resources.

The issue above is that if a server owns the file it also has the responsibility to also hold the metadata and client cache directory. In XFS, they can be handled by separate nodes. So if a server has a ‘hot file’ then it can use all its memory on caching the file content and another server can handle the metadata management.

Another trick XFS implements is cooperative client caching - if a file is being used by 2 or more clients on the same peer network then they can utilise each others file cache instead of needing to go to the server at all.

# Subsetting storage servers

Instead of the logs being stored on the servers, clients build their own log locally. When the log is full or after a given period of time, it writes this out to the servers.

However, instead of writing this log across all servers each client is given a subset of the servers (its stripe group). Then the log is written to the servers associated to it.

This is good as it reduces contention on servers as not all clients are writing to the same servers. Also you increase availability as if some disks fail you don’t effect all your clients. We will talk about later how we can also use this to increase the efficiency of log cleaning as we only need to handle a subset of servers when carrying out a clean.

# Cooperative caching

XFS instead of treating all clients as individuals instead allows them to know about one another and so can share information. It makes two assumptions to do this:

Uses single writer multiple reader (SWMR) protocol for consistency, and

It doesn’t consider files as a whole but instead breaks files into blocks.

Then a server maintaining the metadata for a file block stores all the clients who are reading and if there is a file writer for that block.

When a client wants to write to a block the following happens:

The server tracking the metadata of the block invalidates everyones cache.

It then grants the writer a token saying it is allowed to write to the block, and gives a copy of the latest version of the block.

It then tells all readers the location of the client to get the latest state of the block from the writers cache.

The server can invalidate the token of the writer if it needs to. What happens then is the old writer client hands its changes back to the stripe group for striping. Then the server can establish a new cache for that block and give it out to anyone that needs it.

# Log cleaning

Log cleaning is the process of garbage collecting the logs as described in the LSFS section. In XFS, this happens in a distributed manner - concurrently among the different stripe groups. Each stripe group has a leader who is responsible for garbage collection in that group. The garbage collection also happens on the client side rather than the server side.

TODO: Read the paper to understand the details on this.

# XFS data structures

There are key data structures in XFS:

- Manager map: This maps the file name to the manager responsible for that file. This is a replicated hash table all servers and clients keep a copy of.

The below structures are all kept by the manager node:

File directory: This maps the file name to the i-node number for that file.

i-map: This maps the i-node number to the address that the i-node is stored on.

stripe group map: Maps from address to the storage servers that hold that data.

These then can be used to find the data that relates to this file in the following way.

(Client) + (file name, offset) -> (server node) uses the (manager map) to get the (manager node).

(Client) + (file name, offset) -> (manager node) uses the (file directory) to get the (i-node number).

(Client) + (i-node number) -> (manager node) uses the (i-map) to get the (i-node address).

(Client) + (i-node address) -> (manager node) uses the (stripe group map) to get the (i-node storage server).

(Client) + (i-node address, offset) -> (i-node storage server) looks up the i-node containing the (data addresses).

(Client) + (data address) -> (manager node) uses (stripe group map) to get (data storage server).

(Client) + (data address) -> (data storage server) to get the (data).

This is a very long lookup - however with caching this can be sped up a lot.

# Already seen block

If a client wants to access a filename and offset it has already looked at, this will be stored in a directory locally. Therefore, it can go directly to a local memory cache of that fine. In this path there is no call outs to XFS at all!

# No local cache (with peer)

If a client has been reading a file before, then it will look in the directory for the offset it wants but find a missing cache for this offset. (This can happen for offsets it has read before if another client took the write token for this block.) The client can use the local copy of the manager map to find the manager node responsible for the file - so reaches out to the manager. If the file block is being read/written to by a peer on the network, then the manager informs the client of this location and leave them to get the cache from their peer. It is on the client to then talk to the peer for the latest copy of this block.

This path takes 3 network hops to get the data.

# The long way

This is the path described above - which uses 5 network hops to get the data.

However, this can be cut shorter if the manager has looked up the i-node before and it may have cached the address of the data block. In this case, we cut it down to 3 network hops.