# Week 10 - Failures and Recovery

Last edited: 2025-11-30

# Week 10 - Failures and Recovery

Within an operating system, crashes will occur. When they do they need to leave us in state we can recover from. To do this we need persistence and recovery.

# Lightweight Reliable Virtual Memory (LRVM)

Whilst the operating system and its subsystems are changing objects in memory if a crash occurs before it has a chance to save it to disk it can leave the OS in a broken state. To combat this LRVM creates an interface to make some objects in virtual memory persistent on the disk. The key to this working is to make this fast and have a clean, easy to use interface for subsystem designers.

If the writes to disk where random, this would be slow as disks need to seek to different positions. So instead we use log based writes similar to the distributed file system.

# Interface

Initialisation

initialize(options): Set up the LRVM within this address space.map(region, options): Map some region of virtual memory into persistent storage.unmap(region): Remove a region from persistent storage.

Operations

begin_xact(tid, restore_mode): Start a transaction and get given an id for it.set_range(tid, addr, size): Set what address ranges are going to be edited in this transaction.end_xact(tid, commit_mode): End the transaction and save it down.abort_xact(tid): Abort the transaction and discard it.

Transactions are not immediately reflected in the persistent storage - instead the new value of the memory are stored in a redo log which is saved to the disk for later compaction. The above operations are all developers need to know - however there are a couple more operations if they would like to manually manage when these logs are applied.

Management

flush(): Flush all the redo logs to disk.truncate(): Truncate the log file to the current size.query_options(region): Get the options for a given region.set_options(region, options): Set the options for a given region.create_log(options, len, mode): Manually create a new log file.

# Managing aborts

When the developer calls set_range the LRVM will make a ‘undo record’ of that range.

Then if the transaction is aborted, this copy will be applied to the region to clear any changes made to it.

(This can be toggled off using no_restore mode in the begin_xact call.

This will make LRVM more performant.)

# Managing flushes

In a flush we write to the disk, therefore as a matter of optimisation we may want to hold off flushing until multiple writes are ready.

For this we can set no_flush mode in the end_xact call.

However, this ability to have lazy persistence does leave a window of vulnerability where if a power outage or crash happens whilst redo logs are in memory rather than on disk - there is no recovery from this.

# Crash recovery

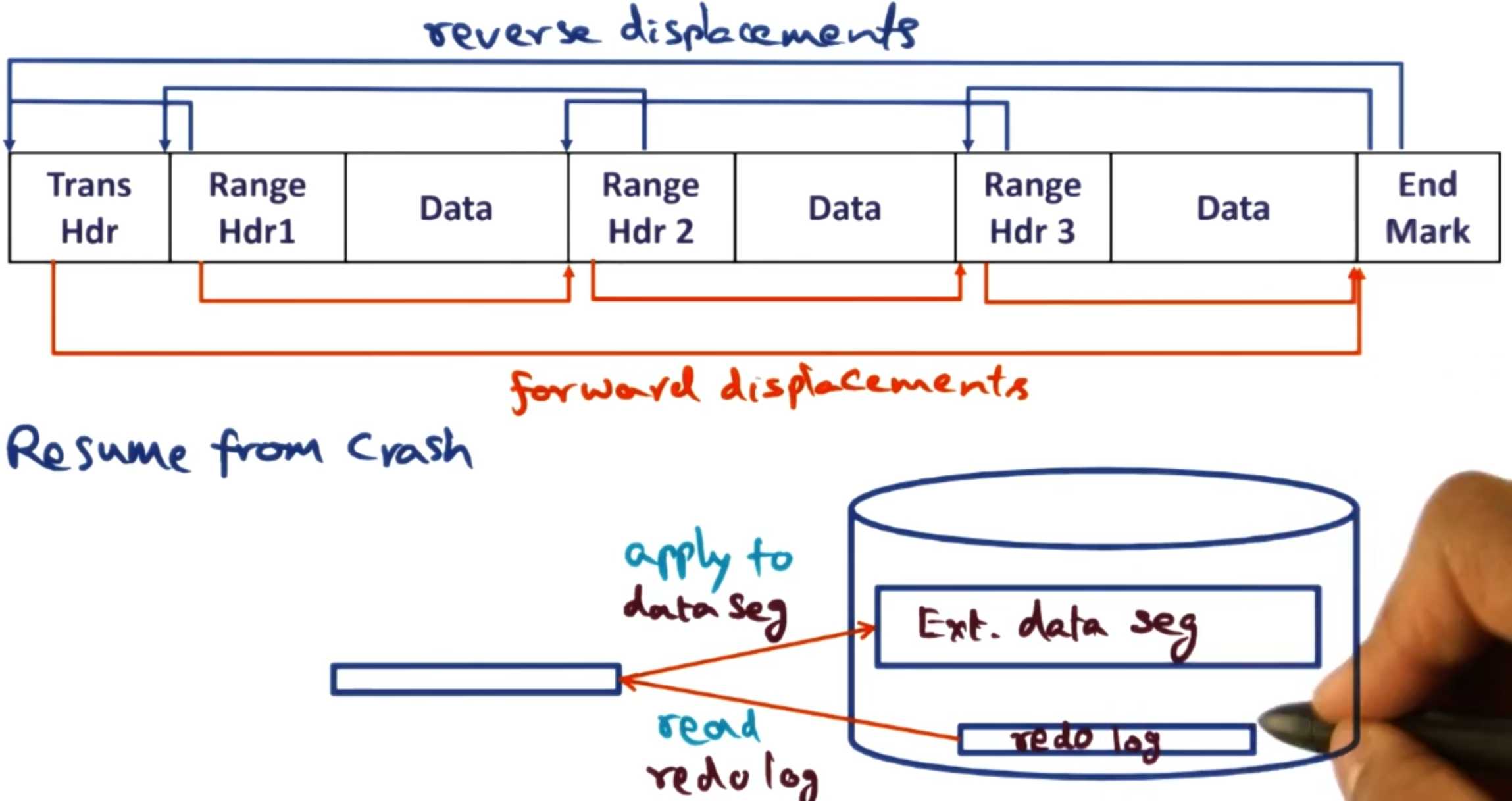

The redo logs are lists of the changes made to the persisted memory status.

These redo logs are saved to disk before being applied to the persistent data structures representing the virtual memory. So if when we restart we find un-applied redo logs we apply these before we reload the memory addresses.

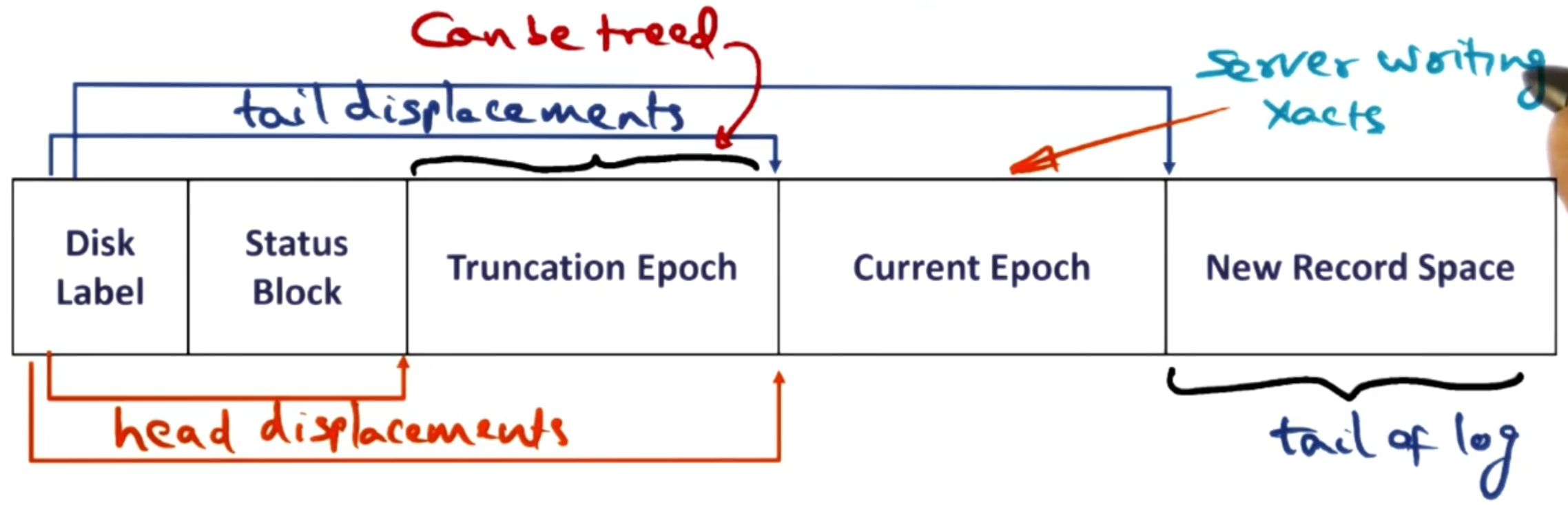

# Log truncation

If we do not crash then we slowly accumulate redo logs on disk - which can take up a lot of disk space. Therefore, there is either the explicit truncate call or the implicit cleanup ran by LRVM.

To run truncation we do as we laid out above. We move the old redo logs to memory, apply them to disk representations. After that we throw away the redo log.

Though we want to do this in parallel to letting the application code running. Therefore, we break the redo logs into epoch’s so we can clean up one epoch at a time whilst letting the application code to add new redo logs to the current epoch. The truncation process is one of the most complex and time consuming parts of LRVM.

# Riovista

There are two sources of system failures:

Power outages: Where the power for the whole system stops.

Software bugs: Where the software causes the machine to crash.

In the LRVM system we handled both these cases. However, if we attach an external battery to our virtual memory we could guarantee the first cause of outages never happens. This is the premise of the Riovista system: We have a portion of main memory which has an external battery and is resilient to crashes, we call this persistent memory.

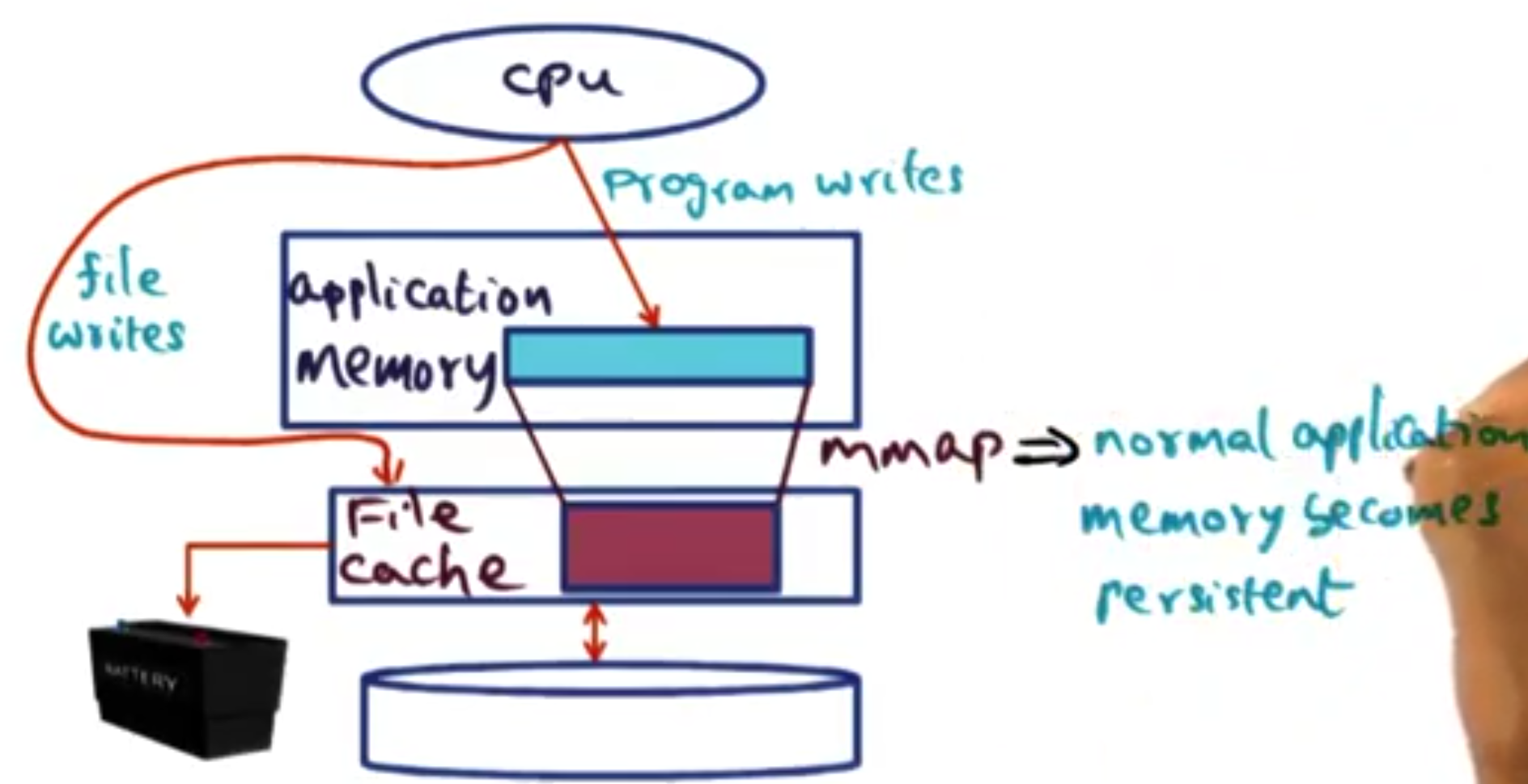

# Rio file cache

A file cache is a in memory representation of a file. This allows for:

Fast writes to a file without needing to go to disk.

Mmapped files to be read and written to in memory - to be reflected on disk later.

If we make the region of this memory that we put the file cache into persistent, we can guarantee these writes will be reflected in the disk eventually. Without the persistent storage, any writes that happen in memory but are not reflected on disk risk failure causing them to be eliminated leaving the disk in a broken state. The Persistent file cache means that synchronous writes to disk no longer need to happen (space allowing). Files that are written to are replicated back to disk after the program has stopped using it.

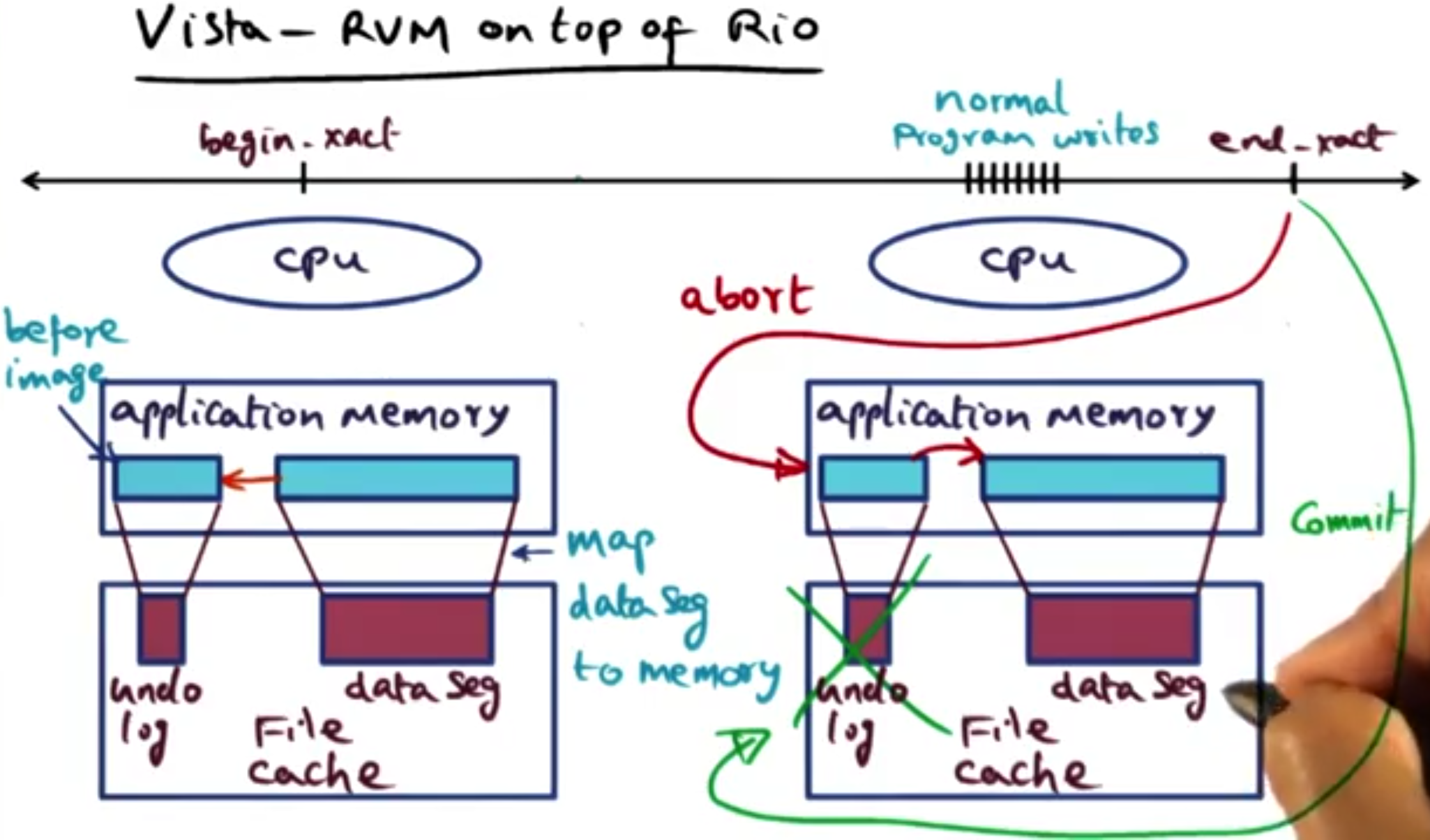

# Vista

Visa is an RVM that is built on top of the Rio file cache.

Vista follows the same interface as LRVM but uses the file cache instead of logs to persist the memory.

When we initialise the persistence of some virtual memory locations, we just back them onto our persistent file cache.

During begin_xact we make an in memory copy of the memory location we are persisting and save it as the undo log in the file cache.

During the critical section, edits are made to the original memory location which are persisted onto the persistent file cache. In the case of a commit we simply delete the undo log and move on. In the case of the abort we copy the undo log back to the original memory location restoring the state to what it was at the beginning of the transaction. We treat system failures as an abort and use the undo log to wipe temporary changes.

This implementation is incredibly simple, a lot of heavy lifting is coming from the file cache. This means that it has 3 orders of magnitude better performance than LRVM. Though it does require having a battery backed persistent memory.

# Quick silver

Both Riovist and LRVM took a narrow view of what crash recovery is. They looked only at the state that needs to be saved during a crash but not what state needs to be cleaned up after a crash. For example, if you use a NFS and they crash your local computer may still have open connections and state reserved for that NFS. This consumes resources and can cause problems. Quicksilver is an OS that takes a recovery first approach to make sure all applications are hygienic.

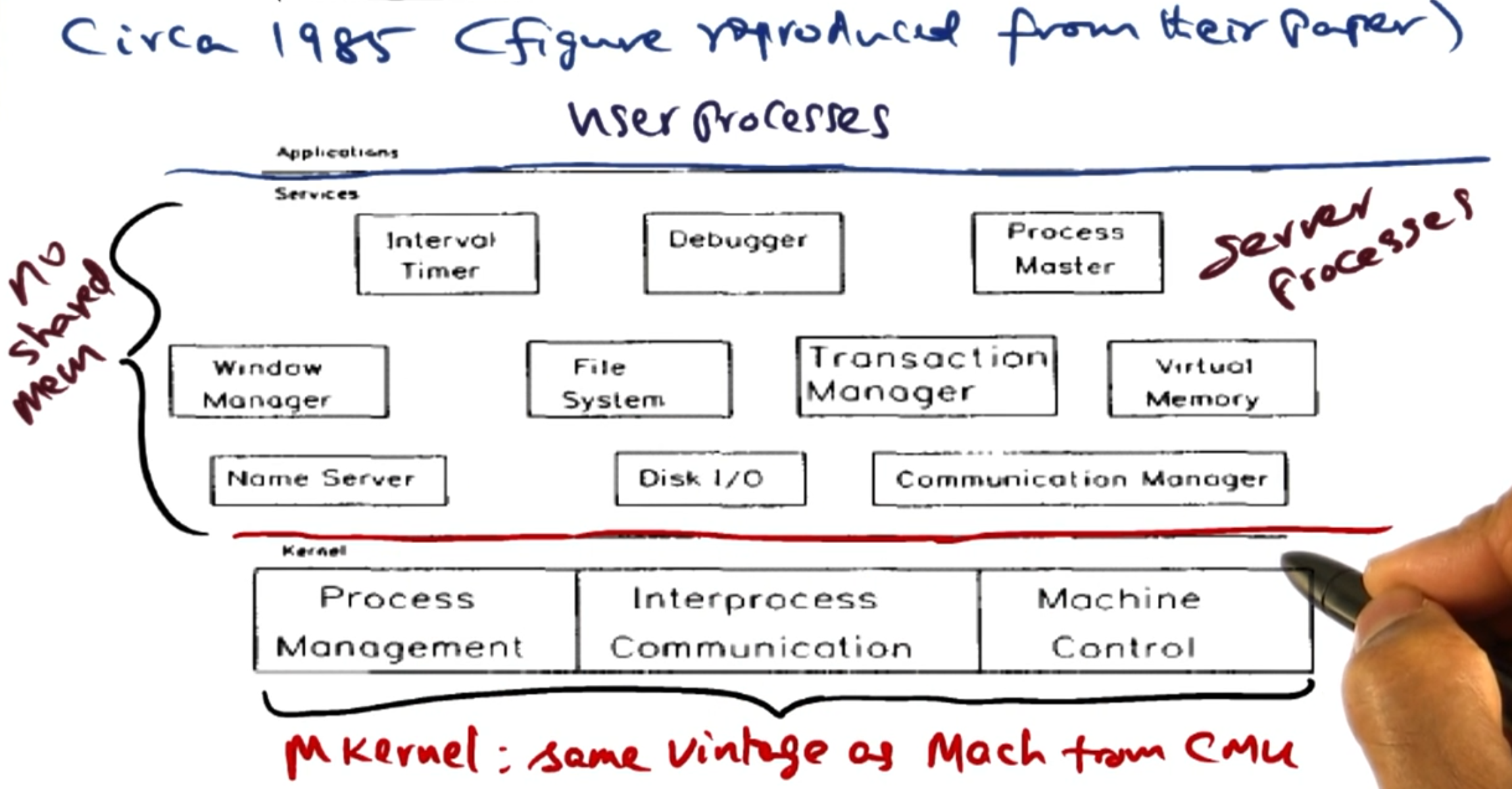

# Quicksilver structure

Quicksilver is built on what is now a typical micro kernel architecture.

For IPC quicksilver uses a service queue structure. This allows clients to put requests on and get responses, as well as for servers to subscribe to the service queue to carry out requests. The OS ensures exactly once semantics, this means no request is dropped and isn’t handled twice. This can be carried out either synchronously or asynchronously - where clients can choose to wait at some point later for the response. Multiple servers can wait on requests, to do this they make an ‘offer’ to the service queue. (Historical note: Quicksilver was developed around the same time as RPC.)

IPC can work across nodes, when requests are made they are managed by a communication manager. This communication manager can choose the communication method that is best for the request that is being made.

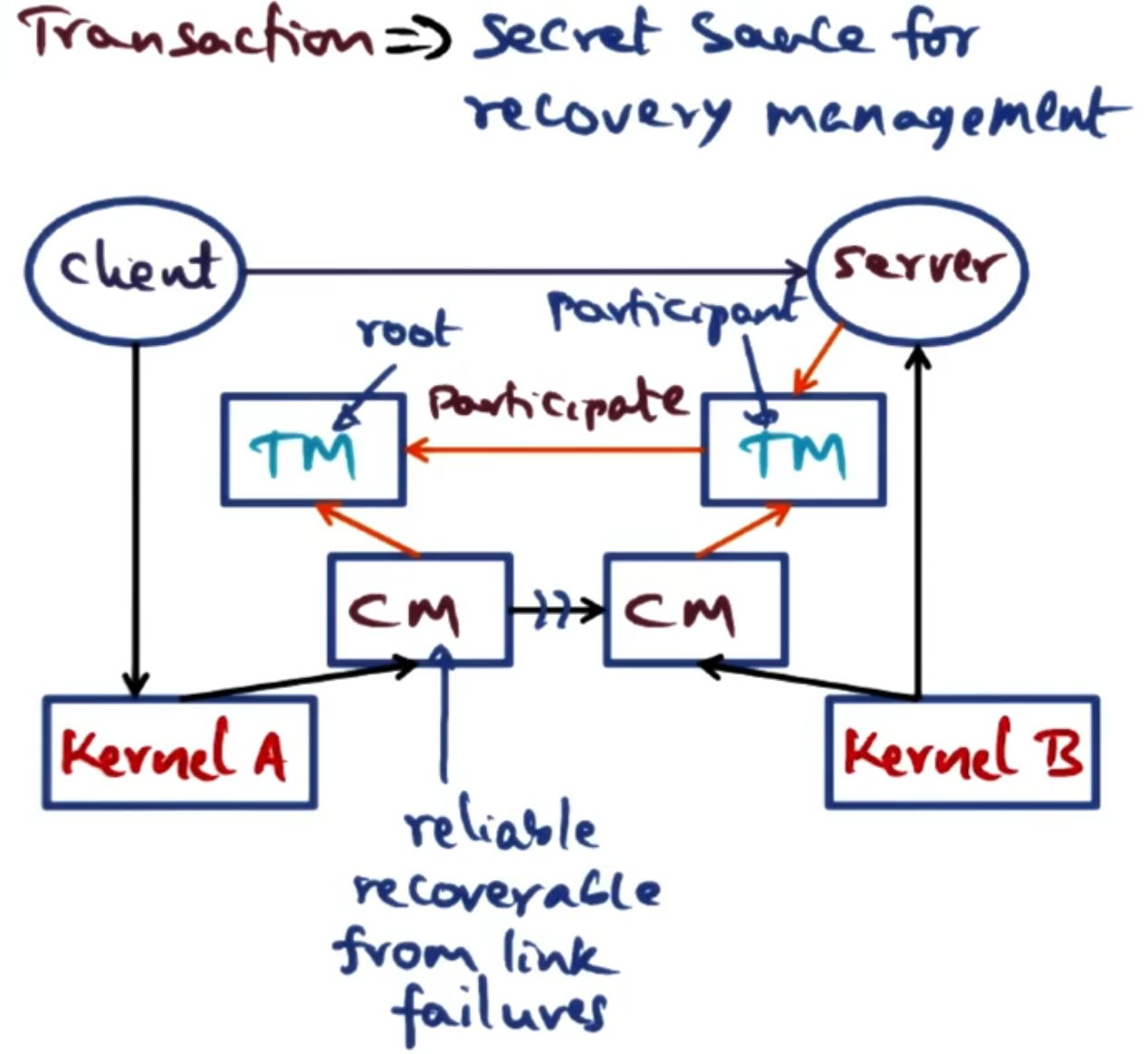

IPC and the communication manager are important for how the recovery mechanism works. When a client talks to a server they both also spin up a transaction manager. It is the clients responsibility for managing transactions, that is recording what happens to the request it makes and propagating that back. As servers can be clients for other services, these naturally form a tree structure of requests that have been made. This way if the transaction is to fail in anyway the client has all the information to clean up after itself.

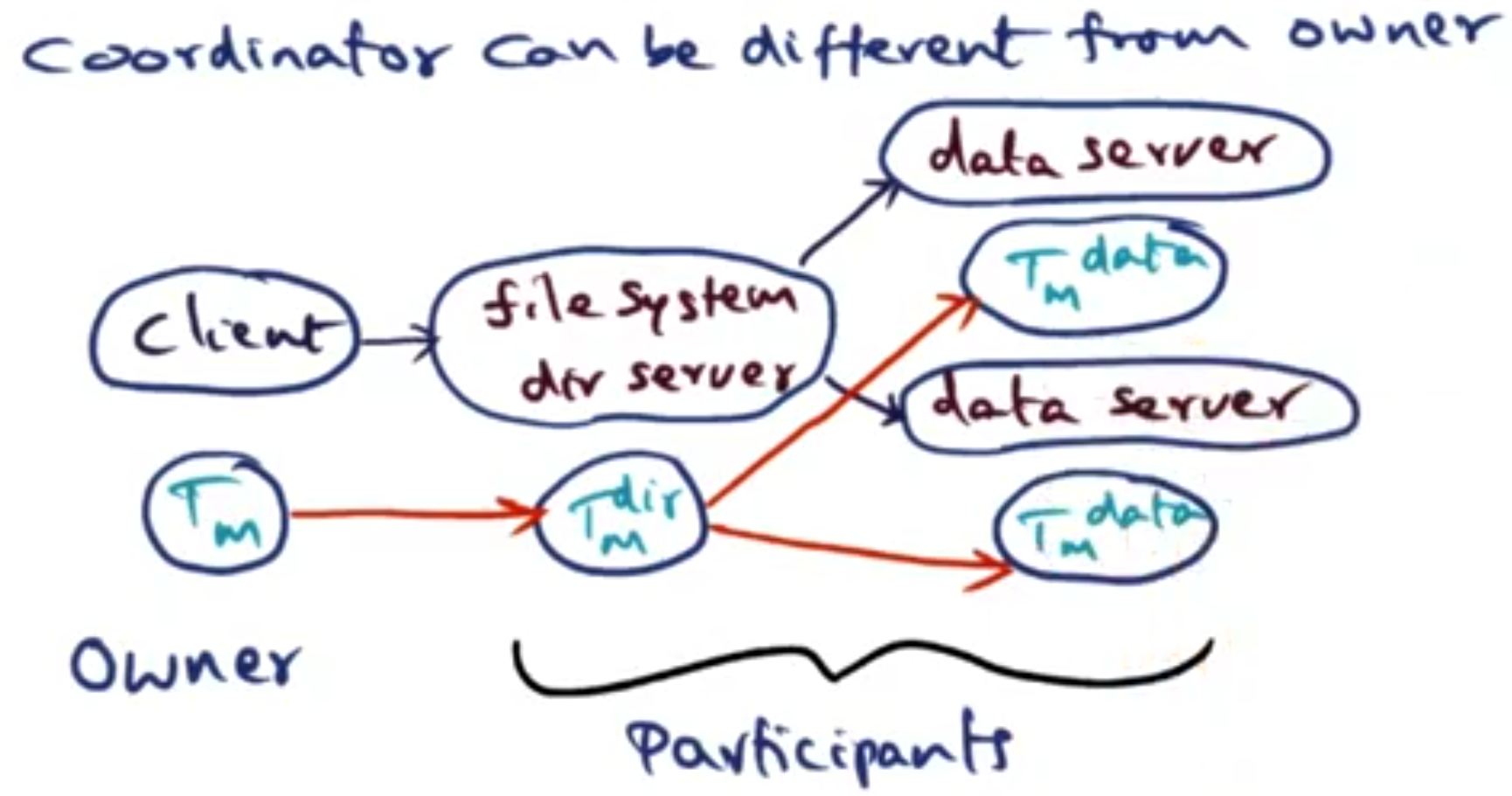

Whilst the client owns the transaction, this may be a risk - due to clients sometimes being the least reliable link in a transaction. Therefore it is possible for the owner to delegate the responsibility of managing this transaction to another node in the system (this will be called a coordinator).

The transaction manager on each node (server/client) saves the part of the transaction it is aware of into local logs into persistent memory. To reduce the amount of network traffic servers just report logs up to the node above it in the transaction tree.

There are different types of failures in the system:

Network failures between nodes.

Node failure.

These all need to be tracked and dealt with by the nodes above them in the system. However, transactions are not aborted by a single failure within the transaction graph. The responsibility for aborting and cleaning up transactions lies with the transaction coordinator (or owner). This means error reporting doesn’t stop due to one failure - you can get more information about the errors if it continues.

Within the transaction tree different messages can be passed up or down the tree. Responses to the requests flow up from servers to clients. However, transaction managers on the client can make 3 requests from the server:

Vote request: If the coordinator wants to commit the transaction, it asks all the nodes to vote on if this request should commit or abort. Notes then respond with vote-commit or vote-abort.

Abort request: Similarly if the coordinator wants to inform nodes that it is aborting the request, it sends an abort request. Then servers say when they are ready to abort the request.

End commit/abort: Lastly to note the request has been fully completed it sends a message to say the commit or abort has completed.

In the case of the transaction origin failing with a different transaction coordinator - in this case the transaction coordinate propagates the abort to all nodes in the transaction tree.

The advantage of bundling the IPC and recovery mechanisms is that the recovery mechanism is simpler. Any failed request you can walk through the nodes and find out what happened. There is also no extra communication for recovery as it comes built into the IPC protocol.

An important note is that the OS implements the mechanism but not the policy itself. It is up to the subsystems to implement the recovery policies it needs for the state it is managing. This allows them to fine tune how impactful this recovery mechanism is on the service. Nodes uses a similar mechanism to LRVM for logs - and it is also up to the node how regularly it needs to write a redo logs to disk. In the Quicksilver case it is possible for clients to do a ’log force’ to make the servers write logs to disk however, this impacts performance for ALL clients of this server.